In addition to the pandemic, 2020 was marked by “the deadliest gun violence in decades.” Since then, the US continues to lead the world in gun violence. Those on the left, broadly construed, profess to want to address gun violence. Those on the right, broadly construed, offer thoughts and prayers after each mass shooting and then obstruct efforts to address gun violence.

In addition to the pandemic, 2020 was marked by “the deadliest gun violence in decades.” Since then, the US continues to lead the world in gun violence. Those on the left, broadly construed, profess to want to address gun violence. Those on the right, broadly construed, offer thoughts and prayers after each mass shooting and then obstruct efforts to address gun violence.

While the right tries to appeal to an inviolable constitutional right they love, this is clearly a bad faith position. After all, the party has been busy restricting voting rights and curtailing liberties and rights they dislike. As such, a true claim would be that the right favors a narrow set of rights for a narrow set of people and gun rights for white people is a major intersection of these sets.

To pre-empt the usual ad hominem and straw man attacks, my backstory as a guy from Maine who grew up hunting and shooting gives me a positive feeling about guns. Subjectively, my gun experiences have been positive, such as hunting with my dad. I am well aware that other people have radically different experiences that shape how they feel about guns.

From a philosophical standpoint, I have also argued in favor of weapon rights as part of the right to self-defense. This justification does, of course, run up against another of my views in political philosophy. Stealing from Locke and Hobbes, I think that we give up some of our rights when we enter civil society and one can make a good case that this can include the right to possess certain weapons. Somewhat ironically, the people who are mistreated by the political and economic systems would have the best claim to possess and use weapons against those who would harm them. This view is generally the exact opposite of what is pushed by the right. A white couple “protecting” themselves from peaceful protestors legally walking by their property are presented by some as heroes. Minorities who seek to arm themselves are seen in a rather different light. As such, when the right tries to block attempts to address gun violence by appeals to rights, they are generally acting in bad faith: they are not principled defenders of rights, they are working to defend very specific rights for very specific people. But on to the focus of this essay.

When laws are proposed to address gun violence, one stock tactic of the right is to bring up Chicago. This city is infamous for its gun violence. The Chicago Tribune has a web page, updated weekly, that provides daily totals of shooting victims in the city. It even has an interactive map that allows people to search for shootings. One cannot deny that the city has a problem with gun violence. My adopted city of Tallahassee also has a crime map, it shows the location of shootings as well.

As one would expect, there have been efforts to address this violence by passing gun control laws. While Illinois does not have the strictest gun laws in the United States (California seems stricter), the laws are stricter than most other states. And yet, as noted above, gun violence is still a serious problem. From this, folks on the right often infer that gun laws do not work. On the face of it, their logic would seem good:

Premise 1: If gun control laws worked, then Chicago would have less gun violence.

Premise 2: Chicago does not have less gun violence.

Conclusion: Gun control laws do not work.

Thus, it is no surprise that the “Chicago Card” is regularly played to “refute” efforts to address gun violence by new laws. Unfortunately, this gambit is a cheat: while the logic seems good, a little consideration shows that it has serious flaws. That this is the case can be shown by the following analogy.

Suppose that you live in an apartment complex and would prefer to not die in a fire. So, you install a smoke detector, you buy a fire extinguisher, you don’t allow open flames in your apartment, you do not store oily rags next to your stove and so on for all the sensible things to do to avoid death by fire. But then your apartment burns and you die in the fire. Using the logic of the right, this is how people should reason:

Premise 1: If fire prevention practices and rules worked, then you would not have died in the fire.

Premise 2: You died in the fire.

Conclusion: Fire prevention practices and rules do not work.

But this seems problematic. Intuitively, these practices and rules would seem to work and should reduce the chances of dying in a fire. So, what went wrong? One possibility is, of course, possibility: things can always go wrong. No sensible person claims that taking precautions against fire will always work. Likewise, the same can happen with gun laws. But, of course, Chicago is place where the metaphorical fires keep occurring—so the idea that it is just bad luck does not hold up. So, we need to look more at the cause of the fires.

Going back to your apartment building, suppose your immediate neighbors also took the same precautions as you, but their apartments were also consumed by fire. If the investigation stopped there, one might conclude that precautions do not matter and having rules about fire safety are pointless. But suppose that the investigators decided to trace the fire to its starting point, and they find the fire began in apartments whose inhabitants took few precautions against fires and some, in fact, engaged in dangerous behavior like leaving burning candles unattended. In this case, the inference would not be that fire prevention and practice do not work. Rather, it would be that to have the best chance of working, then everyone needs to follow these measures. Otherwise, the laxity of some can kill others even if they take precautions.

Chicago is like the apartment where fire safety is practiced. Other states around Illinois are like the apartments without good safety practices. So, just as a fire is more likely to start in those other apartments and spread, guns are likely to come into Chicago from states that have less restrictive rules. As such, Chicago’s gun violence does not prove that restrictions do not work. Rather, it shows that a lack of restrictions in other states can negate restrictions in one state. As such, the Chicago argument is either a bad faith argument, or an a made in ignorance of how things work.

In closing, it might be true that laws would not meaningfully reduce gun violence but pointing to Chicago no more proves that then pointing to a burned-out apartment of a person who was careful about fire proves that fire safety would not meaningfully reduce fire deaths. Now, if everyone practiced fire safety and fire deaths not diminished, then we could conclude that fire safety was useless. Likewise, if all states had restrictive gun laws that were enforced and gun deaths never diminished, then we could conclude they were useless. But this is not the case.

In the face of real problems, the Republican legislature of my adopted state of Florida has been busy addressing fictional problems and undermining democracy. For example,

In the face of real problems, the Republican legislature of my adopted state of Florida has been busy addressing fictional problems and undermining democracy. For example,  As a philosopher, I annoy people in many ways. One is that I almost always qualify the claims I make. This is not to weasel (weakening a claim to protect it from criticism) but because I am aware of my epistemic limitations: as Socrates said, I know that I know nothing. People often prefer claims made with certainty and see expressions of doubt as signs of weakness. Another way I annoy people is by presenting alternatives to my views and providing reasons as to why they might be right. This has a downside of complicating things and can be confusing. Because of these, people often ask me “what do you really believe!?!” I then annoy the person more by noting what I think is probably true but also insisting I can always be wrong. This is for the obvious reason that I can always be wrong. I also annoy people by adjusting my views based on credible changes in available evidence. This really annoys people: one is supposed to stick to one view and adjust the evidence to suit the belief. The origin story of COVID-19 provides an excellent example for discussing this sort of thing.

As a philosopher, I annoy people in many ways. One is that I almost always qualify the claims I make. This is not to weasel (weakening a claim to protect it from criticism) but because I am aware of my epistemic limitations: as Socrates said, I know that I know nothing. People often prefer claims made with certainty and see expressions of doubt as signs of weakness. Another way I annoy people is by presenting alternatives to my views and providing reasons as to why they might be right. This has a downside of complicating things and can be confusing. Because of these, people often ask me “what do you really believe!?!” I then annoy the person more by noting what I think is probably true but also insisting I can always be wrong. This is for the obvious reason that I can always be wrong. I also annoy people by adjusting my views based on credible changes in available evidence. This really annoys people: one is supposed to stick to one view and adjust the evidence to suit the belief. The origin story of COVID-19 provides an excellent example for discussing this sort of thing. Texas’ power infrastructure collapsed in the face of a winter storm, leaving many Texans in the frigid darkness. Ted Cruz infamously fled Texas in search of warmer climes, ensuring his ongoing success as an ideal Republican politician. You might expect that Texans would have responded to this disaster by addressing the underlying problems. You might, if you did not understand the Republicans of Texas.

Texas’ power infrastructure collapsed in the face of a winter storm, leaving many Texans in the frigid darkness. Ted Cruz infamously fled Texas in search of warmer climes, ensuring his ongoing success as an ideal Republican politician. You might expect that Texans would have responded to this disaster by addressing the underlying problems. You might, if you did not understand the Republicans of Texas. In the context of the war on “cancel culture” Republicans professes devotion to the First Amendment, freedom of expression and the marketplace of ideas. As noted in earlier essays, they generally frame such battles in disingenuous ways or lie. For example, Republicans raged against the alleged cancellation of Dr. Seuss, but the truth is Dr. Seuss’ estate decided to stop selling six books. As another example, Republicans went into a frenzy when Hasbro renamed their Mr. Potato Head product line to “Potato Head” while keeping Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head. In these cases, the companies were not forced to do anything, and these seemed to be marketing decisions based on changing consumer tastes and values.

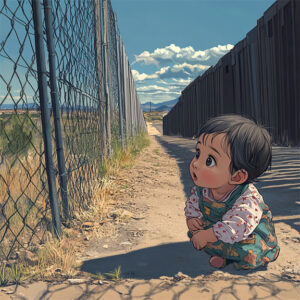

In the context of the war on “cancel culture” Republicans professes devotion to the First Amendment, freedom of expression and the marketplace of ideas. As noted in earlier essays, they generally frame such battles in disingenuous ways or lie. For example, Republicans raged against the alleged cancellation of Dr. Seuss, but the truth is Dr. Seuss’ estate decided to stop selling six books. As another example, Republicans went into a frenzy when Hasbro renamed their Mr. Potato Head product line to “Potato Head” while keeping Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head. In these cases, the companies were not forced to do anything, and these seemed to be marketing decisions based on changing consumer tastes and values. In addition to being evil, bigotry also tends to be repetitive. For example, racists and xenophobes have relentlessly claimed that migrants are diseased job stealing criminals. This has gone on so long in the United States that descendants of migrants who were subject to these bigoted attacks are now using them against the latest wave of migrants. Another classic is the “what about the children!” tactic.

In addition to being evil, bigotry also tends to be repetitive. For example, racists and xenophobes have relentlessly claimed that migrants are diseased job stealing criminals. This has gone on so long in the United States that descendants of migrants who were subject to these bigoted attacks are now using them against the latest wave of migrants. Another classic is the “what about the children!” tactic. If a person dies in the United States and is not in the care of a doctor, then any investigation into their cause of death will probably be conducted by a medical examiner or coroner. To qualify as a medical examiner, a person must be a physician and are often board qualified in forensic pathology. In contrast, most states have only two qualifications for coroner: they must be of legal age and have no felony convictions. Coroners are often elected while medical examiners are usually appointed.

If a person dies in the United States and is not in the care of a doctor, then any investigation into their cause of death will probably be conducted by a medical examiner or coroner. To qualify as a medical examiner, a person must be a physician and are often board qualified in forensic pathology. In contrast, most states have only two qualifications for coroner: they must be of legal age and have no felony convictions. Coroners are often elected while medical examiners are usually appointed.  With a few notable exceptions, Republican politicians backed Trump’s big lie about the 2020 election. Now that Trump is back in office, the big lie has faded into the background. While most Republicans did not deny that Biden was President,

With a few notable exceptions, Republican politicians backed Trump’s big lie about the 2020 election. Now that Trump is back in office, the big lie has faded into the background. While most Republicans did not deny that Biden was President,  While it is tempting to think of politics as the art of lying, I content it works best when done in good faith. This is based on my conventional political philosophy. As would be expected, I accept that the legitimacy of the state rests on the consent of the governed. As thinkers like Locke and Hobbes have advanced better arguments than I can provide, so I simply steal from them. When it comes to consent, I agree with Socrates’ remarks in the Crito. For a person to consent to the rule of the state, they can neither be deceived nor coerced. People must also have the opportunity to provide this consent; in a democracy (or republic) one means of providing consent is by voting and this is why easy and secure voting is essential to the political legitimacy of a democratic state.

While it is tempting to think of politics as the art of lying, I content it works best when done in good faith. This is based on my conventional political philosophy. As would be expected, I accept that the legitimacy of the state rests on the consent of the governed. As thinkers like Locke and Hobbes have advanced better arguments than I can provide, so I simply steal from them. When it comes to consent, I agree with Socrates’ remarks in the Crito. For a person to consent to the rule of the state, they can neither be deceived nor coerced. People must also have the opportunity to provide this consent; in a democracy (or republic) one means of providing consent is by voting and this is why easy and secure voting is essential to the political legitimacy of a democratic state. Since the United States has only two major parties, each includes people with very different political philosophies. For example, Harris differs greatly from Bernie Sanders. The Republican Party has become more ideologically homogenous, but it also contains some degree of diversity. Although the anti-Trump Republicans have been assimilated or purged.

Since the United States has only two major parties, each includes people with very different political philosophies. For example, Harris differs greatly from Bernie Sanders. The Republican Party has become more ideologically homogenous, but it also contains some degree of diversity. Although the anti-Trump Republicans have been assimilated or purged.