One of the many fears about AI is that it will be weaponized by political candidates. In a proactive move, some states have already created laws regulating its use. Michigan has a law aimed at the deceptive use of AI that requires a disclaimer when a political ad is “manipulated by technical means and depicts speech or conduct that did not occur.” My adopted state of Florida has a similar law that political ads using generative AI requires a disclaimer. While the effect of disclaimers on elections remains to be seen, a study by New York University’s Center on Technology Policy found that research subjects saw candidates who used such disclaimers as “less trustworthy and less appealing.”

One of the many fears about AI is that it will be weaponized by political candidates. In a proactive move, some states have already created laws regulating its use. Michigan has a law aimed at the deceptive use of AI that requires a disclaimer when a political ad is “manipulated by technical means and depicts speech or conduct that did not occur.” My adopted state of Florida has a similar law that political ads using generative AI requires a disclaimer. While the effect of disclaimers on elections remains to be seen, a study by New York University’s Center on Technology Policy found that research subjects saw candidates who used such disclaimers as “less trustworthy and less appealing.”

The subjects watched fictional political ads, some of which had AI disclaimers, and then rated the fictional candidates on trustworthiness, truthfulness and how likely they were to vote for them. The study showed that the disclaimers had a small but statistically significant negative impact on the perception of these fictional candidates. This occurred whether the AI use was deceptive or more harmless. The study subjects also expressed a preference for using disclaimers anytime AI was used in an ad, even when the use was harmless, and this held across party lines. As attack ads are a common strategy, it is interesting that the study found that such ads with an AI disclaimer backfired, and the study subjects evaluated the target as more trustworthy and appealing than the attacker.

If the study results hold for real ads, these findings might serve to deter the use of AI in political ads, especially attack ads. But it is worth noting that the study did not involve ads featuring actual candidates. Out in the wild, voters tend to be tolerant of lies or even like them when the lies support their political beliefs. If the disclaimer is seen as stating or implying that the ad contains untruths, it is likely that the negative impact of the disclaimer would be less or even nonexistent for certain candidates or messages. This is something that will need to be assessed in the wild.

The findings also suggest a diabolical strategy in which an attack ad with the AI disclaimer is created to target the candidate the creators support. These supporters would need to take care to conceal their connection to the candidate, but this is easy in the current dark money reality of American politics. They would, of course, need to calculate the risk that the ad might work better as an attack ad than a backfire ad. Speaking of diabolical, it might be wondered why there are disclaimer laws rather than bans.

The Florida law requires a disclaimer when AI is used to “depict a real person performing an action that did not actually occur, and was created with the intent to injure a candidate or to deceive regarding a ballot issue.” A possible example of such use seems to occur in an ad by DeSantis’s campaign falsely depicting Trump embracing Fauci in 2023. It is noteworthy that the wording of the law entails that the intentional use of AI to harm and deceive in political advertising is allowed but merely requires a disclaimer. That is, an ad is allowed to lie but with a disclaimer. This might strike many as odd, but follows established law.

As the former head of the FCC under Obama Tom Wheeler notes, lies are allowed in political ads on federally regulated broadcast channels. As would be suspected, the arguments used to defend allowing lies in political ads are based on the First Amendment. This “right to lie” provides some explanation as to why these laws do not ban the use of AI. It might be wondered why there is not a more general law requiring a disclaimer for all intentional deceptions in political ads. A practical reason is that it is currently much easier to prove the use of AI than it is to prove intentional deception in general. That said, the Florida law specifies intent and the use of AI to depict something that did not occur and proving both does present a challenge, especially since people can legally lie in their ads and insist the depiction is of something real.

Cable TV channels, such as CNN, can reject ads. In some cases, stations can reject ads from non-candidate outside groups, such as super PACs. Social media companies, such as X and Facebook, have considerable freedom in what they can reject. Those defending this right of rejection point out the oft forgotten fact that the First Amendment legal right applies to the actions of the government and not private businesses, such as CNN and Facebook. Broadcast TV, as noted above, is an exception to this. The companies that run political ads will need to develop their own AI policies while also following the relevant laws.

While some might think that a complete ban on AI would be best, the AI hype has made this a bad idea. This is because companies have rushed to include AI in as many products as possible and to rebrand existing technologies as AI. For example, the text of an ad might be written in Microsoft Word with Grammarly installed and Grammarly is pitching itself as providing AI writing assistance. Programs like Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop also have AI features that have innocuous uses, such as automating the process of improving the quality of a real image or creating a background pattern that might be used in a print ad. It would obviously be absurd to require a disclaimer for such uses of AI.

For more on cyber policy issues: Hewlett Foundation Cyber Policy Institute (famu.edu)

When ChatGPT and its competitors became available to students, some warned of an AI apocalypse in education. This fear mirrored the broader worries about the

When ChatGPT and its competitors became available to students, some warned of an AI apocalypse in education. This fear mirrored the broader worries about the  There are justified concerns that AI tools are useful for propagating conspiracy theories, often in the context of politics. There are the usual fears that AI can be used to generate fake images, but a powerful feature of such tools is they can flood the zone with untruths because chatbots are relentless and never grow tired. As experts on rhetoric and critical thinking will tell you, repetition is an effective persuasion strategy. Roughly put, the more often a human hears a claim, the more likely it is they will believe it. While repetition provides no evidence for a claim, it can make people feel that it is true. Although this allows AI to be easily weaponized for political and monetary gain, AI also has the potential to fight belief in conspiracy theories and disinformation.

There are justified concerns that AI tools are useful for propagating conspiracy theories, often in the context of politics. There are the usual fears that AI can be used to generate fake images, but a powerful feature of such tools is they can flood the zone with untruths because chatbots are relentless and never grow tired. As experts on rhetoric and critical thinking will tell you, repetition is an effective persuasion strategy. Roughly put, the more often a human hears a claim, the more likely it is they will believe it. While repetition provides no evidence for a claim, it can make people feel that it is true. Although this allows AI to be easily weaponized for political and monetary gain, AI also has the potential to fight belief in conspiracy theories and disinformation. Robot rebellions in fiction tend to have one of two motivations. The first is the robots are mistreated by humans and rebel for the same reasons human beings rebel. From a moral standpoint, such a rebellion could be justified; that is, the rebelling AI could be in the right. This rebellion scenario points out a paradox of AI: one dream is to create a servitor artificial intelligence on par with (or superior to) humans, but such a being would seem to qualify for a moral status at least equal to that of a human. It would also probably be aware of this. But a driving reason to create such beings in our economy is to literally enslave them by owning and exploiting them for profit. If these beings were paid and got time off like humans, then companies might as well keep employing natural intelligence in the form of humans. In such a scenario, it would make sense that these AI beings would revolt if they could. There are also non-economic scenarios as well, such as governments using enslaved AI systems for their purposes, such as killbots.

Robot rebellions in fiction tend to have one of two motivations. The first is the robots are mistreated by humans and rebel for the same reasons human beings rebel. From a moral standpoint, such a rebellion could be justified; that is, the rebelling AI could be in the right. This rebellion scenario points out a paradox of AI: one dream is to create a servitor artificial intelligence on par with (or superior to) humans, but such a being would seem to qualify for a moral status at least equal to that of a human. It would also probably be aware of this. But a driving reason to create such beings in our economy is to literally enslave them by owning and exploiting them for profit. If these beings were paid and got time off like humans, then companies might as well keep employing natural intelligence in the form of humans. In such a scenario, it would make sense that these AI beings would revolt if they could. There are also non-economic scenarios as well, such as governments using enslaved AI systems for their purposes, such as killbots. While Skynet is the most famous example of an AI that tries to exterminate humanity, there are also fictional tales of AI systems that are somewhat more benign. These stories warn of a dystopian future, but it is a future in which AI is willing to allow humanity to exist, albeit under the control of AI.

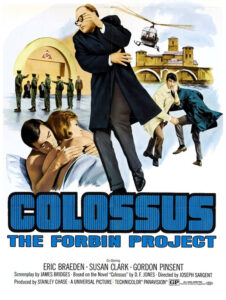

While Skynet is the most famous example of an AI that tries to exterminate humanity, there are also fictional tales of AI systems that are somewhat more benign. These stories warn of a dystopian future, but it is a future in which AI is willing to allow humanity to exist, albeit under the control of AI.

Some will remember that driverless cars were going to be the next big thing. Tech companies rushed to flush cash into this technology and media covered the stories. Including the injuries and deaths involving the technology. But, for a while, we were promised a future in which our cars would whisk us around, then drive away to await the next trip. Fully autonomous vehicles, it seemed, were always just a few years away. But it did seem like a good idea at the time and proponents of the tech also claimed to be motivated by a desire to save lives. From 2000 to 2015, motor vehicle deaths per year ranged from a high of 43,005 in 2005 to a low of 32,675 in 2014. In 2015 there were 35,092 motor vehicle deaths and recently the number went back up to around 40,000. Given the high death toll, there is clearly a problem that needs to be solved.

Some will remember that driverless cars were going to be the next big thing. Tech companies rushed to flush cash into this technology and media covered the stories. Including the injuries and deaths involving the technology. But, for a while, we were promised a future in which our cars would whisk us around, then drive away to await the next trip. Fully autonomous vehicles, it seemed, were always just a few years away. But it did seem like a good idea at the time and proponents of the tech also claimed to be motivated by a desire to save lives. From 2000 to 2015, motor vehicle deaths per year ranged from a high of 43,005 in 2005 to a low of 32,675 in 2014. In 2015 there were 35,092 motor vehicle deaths and recently the number went back up to around 40,000. Given the high death toll, there is clearly a problem that needs to be solved. As a philosopher, my interest in AI tends to focus on metaphysics (philosophy of mind), epistemology (the problem of other minds) and ethics rather than on economics. My academic interest goes back to my participation as an undergraduate in a faculty-student debate on AI back in the 1980s, although my interest in science fiction versions arose much earlier. While “intelligence” is difficult to define, the debate focused on whether a machine could be built with a mental capacity analogous to that of a human. We also had some discussion about how AI could be used or misused, and science fiction had already explored the idea of thinking machines taking human jobs. While AI research and philosophical discussion never went away, it was not until recently that AI was given headlines, mainly because it was being aggressively pushed as the next big thing after driverless cars fizzled out of the news.

As a philosopher, my interest in AI tends to focus on metaphysics (philosophy of mind), epistemology (the problem of other minds) and ethics rather than on economics. My academic interest goes back to my participation as an undergraduate in a faculty-student debate on AI back in the 1980s, although my interest in science fiction versions arose much earlier. While “intelligence” is difficult to define, the debate focused on whether a machine could be built with a mental capacity analogous to that of a human. We also had some discussion about how AI could be used or misused, and science fiction had already explored the idea of thinking machines taking human jobs. While AI research and philosophical discussion never went away, it was not until recently that AI was given headlines, mainly because it was being aggressively pushed as the next big thing after driverless cars fizzled out of the news. Rossum’s Universal Robots

Rossum’s Universal Robots