For years, the right passed anti-choice laws in the hope they would end up in the Supreme Court and lead to the overturning of Roe v Wade. They finally succeeded and anti-abortion groups claimed a major victory over the will of the people.

For years, the right passed anti-choice laws in the hope they would end up in the Supreme Court and lead to the overturning of Roe v Wade. They finally succeeded and anti-abortion groups claimed a major victory over the will of the people.

While purporting to be motivated by pro-life (or at least anti-death) principles, these laws and bills are fundamentally misogynistic. They have three fundamental functions. The first is to appease a key portion of the base.

Second, couched in pro-life language, these laws provide excellent dog whistles for misogynists. The male misogynists generally understand that the message being sent to them is: “Your baby in her body. Her body in your kitchen. Making you a sandwich to put in your body.” More generally, the laws say to the misogynists in the base “we are misogynists like you, and we will put women in their proper place.” Naturally, to make these claims is to seem crazy in the eyes of the “normies.”

Third, the laws codify misogyny by harming women. To be fair, I can add a fourth reason that brings in the Democrats: the abortion debate was something of a battlefield of deceit in which the Republicans falsely claim to be pro-life (or at least anti-death) and the mainstream Democrats agreed to fight the battle on this assumption. The Democrats rhetoric is that they are pro-choice and the mainstream never seems inclined to get into a substantial and complex fight over the core ethical and political issues. That is, of course, broadly true across mainstream politics: politicians mouthing their fighting words while keeping the status quo stable and themselves in power. But it could be objected that I am mischaracterizing things.

One objection is that while some misogynists might support these laws, proponents of anti-abortion laws, such as Alabama governor Kay Ivey, claim their motivation is to protect life. As the governor said, “to the bill’s many supporters, this legislation stands as a powerful testament to Alabamians’ deeply held belief that every life is precious and that every life is a sacred gift from God.” But this is a bad faith claim.

Given the professed view that Alabamans regard life as a precious, sacred gift, one should be shocked to learn that Alabama is terrible in terms of maternal and infant health. Alabama is tied for 4th worst in the United States, with 7.4 deaths per 1,000 live births. While it might be argued that this is due to factors beyond their control, there is a consistent correlation between strong anti-abortion laws and poor maternal and infant health. While correlation is not causation, the reason for this correlation is clear: the state governments that enact the strictest anti-abortion laws also show, via public policies, the least concern for maternal and infant health. Texas, as should surprise no one, also has a high maternal mortality rate. While not nearly as bad as Texas and Alabama, Florida also has a high maternal (and infant) mortality rate.

This is inconsistent with the professed principle that life is a precious, sacred gift. It is also inconsistent with the professed motivation for anti-abortion laws: to protect the life of children. It is, however, consistent with the hypothesis that anti-abortion laws are largely motivated by misogynistic principles. After all, if legislators pass anti-abortion laws because of hostility towards women’s reproductive freedom and wellbeing, then one would also expect them to neglect maternal and infant health in their other policies. On the face of it, this is the better explanation.

Another objection is that the laws are aimed at reducing the number of abortions and this is not misogynistic. Again, it just so happens that it impacts women. The easy and obvious reply is that the most effective way to reduce abortions is to reduce the need for them. Improved sex education and easy and free access to birth control reduces unwanted pregnancies. One might assert that anti-abortion folks also tend to oppose sex ed and birth control; but these are also usually misogynistic positions as well. Defending misogyny with more misogyny is hardly a good defense against an accusation of misogyny.

For those who oppose sex-ed and birth control without being misogynists, one can argue for using social programs to provide women and girls with adequate resources to complete a pregnancy and raise the child. But, as is well known, the anti-abortion folks tend to be savage opponents of programs that help mothers and children. If they were so devoted to life that they think the state should use its coercive power to take control over women, then they should be on board with providing basic state support to enable more women to choose to complete their pregnancy. But the easy and obvious explanation is that the pro-life claims are bad faith assertions; they are not pro-life but are misogynists.

A final objection is to point to women who support anti-abortion laws. Surely, one might say, women would not support misogynist laws. And, of course, men involved with the laws can point out that they have a mother and some of their best friends are women. So how can they be misogynists?

In some cases, women support such laws from ignorance. That is, they accept the bad faith reasons and think that they are supporting the protection of life, not realizing the misogynist consequences of the laws. Interestingly, women on the right are sometimes shocked that the right is misogynistic. They apparently fail to grasp that racism and sexism are the peanut butter and chocolate of the right. In other cases, they might be aware that the laws are advanced in bad faith but agree with the stated goal of restricting abortion. So, they go along with the misogyny because it gets them something they want.

A third possibility is that a woman is herself a misogynist—while this might sound odd, it can happen. Finally, a woman might be an opportunist rather than ignorant or a misogynist—she has calculated that she will gain more as an individual by backing misogyny than she will lose as a woman. So, for example, a female judge or politician might recognize that the right is fundamentally misogynistic but decide that she gains a personal advantage by joining them. Just as the folks on the right desire a few minorities to provide them with a “black friend” as a shield against accusations of racism, they also want a few women to provide them with a shield against accusations of sexism.

Somewhat ironically, the powerful women on the right represent something radical that undermines the right: they hold these positions of power because of the past battles fought by the left. Also, capable women in power give lie to the misogyny of the right (and left). Not so long ago, the right (and left) was openly misogynistic; but this has changed and there is a strong reaction to this shift. It is, of course, ironic that the women who occupy their positions of power due to the fight against misogyny are fighting so hard to roll back the clock for women in general. Perhaps they think that they will retire before the clock is rolled back. Perhaps they are unaware of the consequences of what they are fighting for. Or perhaps they sincerely believe that they should not have been allowed to be where they chose to be and that future women should not be allowed this choice. Or perhaps they know that they will remain the exception to the oppression they wish to impose on other women.

It might be wondered why anyone would bother making the arguments I have made. After all, the right and their supporters are either already aware of the misogynistic purpose of the laws or will not believe me. But there seems to be some value in attempting to reveal that the right’s arguments are in bad faith. There is a slight chance that some people might change their minds about supporting such bad faith laws.

It also seems desirable to try to reveal the bad faith on the right. For example, when they engage in their bad faith arguments and rhetoric about protecting life, that would be the ideal time to call them out on their lack of support (and opposition) to laws that do protect children. These include regulating pollutants that kill children, providing stronger social support for children, ensuring clean water and adequate food for children, providing quality education for children, ensuring quality health care for children, and so on for so many things the “pro-life” right fights. Whenever a right-wing politician proposes a “pro-life” bill, the left should immediately try to add real pro-life components, such as funding for maternal care and the health of children. When a “pro-life” governor is professing their love of life, they should be asked about the infant and maternal mortality rates in their state. And so on.

In fiction, race/gender swapping occurs when an established character’s race or gender is changed. For example, the original Nick Fury character in Marvel is a white man but was changed to a black man in the Ultimates and in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. As another example, the original Dr. Smith in the TV show Lost in Space is a man; the Netflix reboot made the character a woman. As would be expected, some people are enraged when a swap occurs. Some are open about their racist or sexist reasons for their anger and are clear that they do not want females and non-white people in certain roles. Some criticize a swap by asking why there was a swap instead of either creating a new character or focusing on a less well-known existing character. For example,

In fiction, race/gender swapping occurs when an established character’s race or gender is changed. For example, the original Nick Fury character in Marvel is a white man but was changed to a black man in the Ultimates and in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. As another example, the original Dr. Smith in the TV show Lost in Space is a man; the Netflix reboot made the character a woman. As would be expected, some people are enraged when a swap occurs. Some are open about their racist or sexist reasons for their anger and are clear that they do not want females and non-white people in certain roles. Some criticize a swap by asking why there was a swap instead of either creating a new character or focusing on a less well-known existing character. For example,

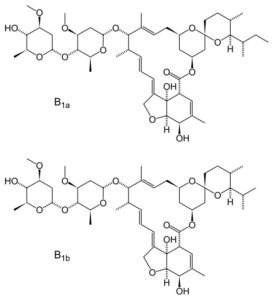

During the last pandemic, Americans who chose to forgo vaccination were hard hit by COVID. In response, some self-medicated with ivermectin. While this drug is best known as a horse de-wormer, it is also used to treat humans for a variety of conditions and many medications are used to treat conditions they were not originally intended to treat. Viagra is a famous example of this. As such, the idea of re-purposing a medication is not itself foolish. But there are obvious problems with taking ivermectin to treat COVID. T

During the last pandemic, Americans who chose to forgo vaccination were hard hit by COVID. In response, some self-medicated with ivermectin. While this drug is best known as a horse de-wormer, it is also used to treat humans for a variety of conditions and many medications are used to treat conditions they were not originally intended to treat. Viagra is a famous example of this. As such, the idea of re-purposing a medication is not itself foolish. But there are obvious problems with taking ivermectin to treat COVID. T First, while an abortion kills an entity there is good faith moral debate about whether the entity is a person. In contrast, a person who did not get vaccinated during the pandemic put those who are indisputably people at risk and, in many cases, without their choice or consent. One can, of course, argue that the aborted entity is a person and start up the anti-abortion debate. But this would have an interesting consequence.

First, while an abortion kills an entity there is good faith moral debate about whether the entity is a person. In contrast, a person who did not get vaccinated during the pandemic put those who are indisputably people at risk and, in many cases, without their choice or consent. One can, of course, argue that the aborted entity is a person and start up the anti-abortion debate. But this would have an interesting consequence. Because of the psychological power of rhetoric, words do matter. Words have both a denotation (the meaning) and a connotation (the emotions and associations invoked). Words that have the same denotation can have very different connotations. For example, “police officer” and “pig” (as slang) have the same denotation but different connotations. As would be expected, the ongoing fight over vaccines involves rhetoric. One interesting example of this was presented by Ben Irvine:

Because of the psychological power of rhetoric, words do matter. Words have both a denotation (the meaning) and a connotation (the emotions and associations invoked). Words that have the same denotation can have very different connotations. For example, “police officer” and “pig” (as slang) have the same denotation but different connotations. As would be expected, the ongoing fight over vaccines involves rhetoric. One interesting example of this was presented by Ben Irvine:  In the last pandemic Americans were caught up in a political battle over masks. Those who opposed mask mandates tended to be on the right; those who accepted mask mandates (and wearing masks) tended to be on the left. One interesting approach to the mask debate by some on the right was to draw an analogy between the mask mandate and the restrictive voting laws that the Republicans have passed. The gist is that if the left opposed the voting laws, then they should have opposed mask mandates. Before getting into the details of the argument, let us look at the general form of the analogical argument.

In the last pandemic Americans were caught up in a political battle over masks. Those who opposed mask mandates tended to be on the right; those who accepted mask mandates (and wearing masks) tended to be on the left. One interesting approach to the mask debate by some on the right was to draw an analogy between the mask mandate and the restrictive voting laws that the Republicans have passed. The gist is that if the left opposed the voting laws, then they should have opposed mask mandates. Before getting into the details of the argument, let us look at the general form of the analogical argument. While Republican politicians in my adopted state of Florida profess to love freedom, they have been busy passing laws to restrict freedom. During the last pandemic Governor DeSantis opposed mask mandates and vaccine passports on the professed grounds of fighting “medical authoritarianism.” He also engaged in the usual Republican attacks on cancel culture, claiming to be a supporter of free speech. However, the Governor and the Republican dominated state legislature banned ‘critical race theory’ from public schools, mandated a survey of the political beliefs of faculty and students, and engaged in book banning. On the face of it, the freedom loving Republicans appear to be waging war on freedom. One could spend hours presenting examples of the apparent inconsistencies between Republican value claims and their actions, but my focus here is on value vagueness.

While Republican politicians in my adopted state of Florida profess to love freedom, they have been busy passing laws to restrict freedom. During the last pandemic Governor DeSantis opposed mask mandates and vaccine passports on the professed grounds of fighting “medical authoritarianism.” He also engaged in the usual Republican attacks on cancel culture, claiming to be a supporter of free speech. However, the Governor and the Republican dominated state legislature banned ‘critical race theory’ from public schools, mandated a survey of the political beliefs of faculty and students, and engaged in book banning. On the face of it, the freedom loving Republicans appear to be waging war on freedom. One could spend hours presenting examples of the apparent inconsistencies between Republican value claims and their actions, but my focus here is on value vagueness. , and they have cast the woke elite as the generals of this opposing force. “Wokeness”, like “cancel culture” and “critical race theory”, is ill-defined and used as a vague catch-all for things the right does not like. In large part, the war on wokeness has been manufactured by the right’s elite. In part, the war arises from grievances of the base. There are even some non-imaginary conflicts in this war —at least on the part of the Americans that can be seen as blue-collar workers. I will be focusing on this and will try to define the groups and harms as clearly and honestly as possible.

, and they have cast the woke elite as the generals of this opposing force. “Wokeness”, like “cancel culture” and “critical race theory”, is ill-defined and used as a vague catch-all for things the right does not like. In large part, the war on wokeness has been manufactured by the right’s elite. In part, the war arises from grievances of the base. There are even some non-imaginary conflicts in this war —at least on the part of the Americans that can be seen as blue-collar workers. I will be focusing on this and will try to define the groups and harms as clearly and honestly as possible. When it comes to pollution, people respond with a cry of

When it comes to pollution, people respond with a cry of