In the previous essay I drew an analogy between the ethics of abortion and the ethics of migration. In this essay, I will develop the analogy more and do so with a focus on the logic of the analogy. Because everyone loves logic.

In the previous essay I drew an analogy between the ethics of abortion and the ethics of migration. In this essay, I will develop the analogy more and do so with a focus on the logic of the analogy. Because everyone loves logic.

Strictly presented, an analogical argument will have three premises and a conclusion. The first two premises (attempt to) establish the analogy by showing that the things in question are similar in certain respects. The third premise establishes the additional fact known about one thing and the conclusion asserts that because the two things are alike in other respects, they are alike in this additional respect. Here is the form of the argument:

Premise 1: X has properties P, Q, and R.

Premise 2: Y has properties P, Q, and R.

Premise 3: X has property Z as well.

Conclusion: Y has property Z

X and Y are variables that stand for whatever is being compared, such as rats and humans or Hitler and that politician you hate. P, Q, R, and Z are also variables, but they stand for properties or qualities, such as having a heart. The use of P, Q, and R is just for the sake of the illustration as the things being compared might have more properties in common.

It is easy to make a moral argument using an argument from analogy. To argue that Y is morally wrong, find an X that is already accepted as being wrong and show how Y is like X. To argue that Y is morally good, find an X that is already accepted as morally good and show how Y is like X. To be a bit more formal, here is how the argument would look:

Premise 1: X has properties P, Q, and R.

Premise 2: Y has properties P, Q, and R.

Premise 3: X is morally good (or morally wrong).

Conclusion: Y is morally good (or morally wrong).

The strength of an analogical argument depends on three factors. To the degree that an analogical argument meets these standards it is a strong argument. If it fails to meet these standards, then it is weak. If it is weak enough, then it would be fallacious. There is no exact point at which an analogical argument becomes fallacious, however the standards do provide an objective basis for making this assessment.

First, the more properties X and Y have in common, the better the argument. This standard is based on the commonsense notion that the more two things are alike in other ways, the more likely it is that they will be alike in some other way. It should be noted that even if the two things are very much alike in many respects, there is still the possibility that they are not alike regarding Z.

Second, the more relevant the shared properties are to property Z, the stronger the argument. A specific property, for example P, is relevant to property Z if the presence or absence of P affects the likelihood that Z will be present.

Third, it must be determined whether X and Y have relevant dissimilarities as well as similarities. The more dissimilarities and the more relevant they are, the weaker the argument.

In the case of drawing a moral analogy between the ethics of abortion and migration, the challenges are to determine the properties that make them alike and to establish the relevant moral status of abortion.

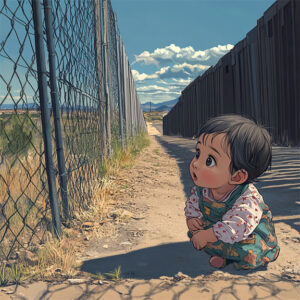

Since my goal is to show that those who already think abortion is morally wrong should also think expelling migrant children is wrong, I can assume (for the sake of the argument) that abortion is wrong. The next step is showing that abortion and expelling migrant children are alike enough to create a strong analogy.

Opponents of abortion tend to argue that human life has intrinsic worth and often speak in terms of a life being precious and a sacred gift from God. Since they tend to believe that a child exists at or soon after conception, it follows that the wrongness of abortion stems from the harm done to that precious life and sacred gift. While some opponents of abortion do allow exceptions for incest and rape, some do not and reject abortion even if the pregnancy occurs against the mother’s will. Obviously enough, all opponents of abortion agree that in most cases the mother should be compelled to bear the child, even if they do not want to and even when doing so would cause them some harm. One way to see this is that the child has a right to remain where it is, even when it got there without the consent of the owner of the womb (the mother) and when she does not want it to remain. What, then, are the similarities between abortion and expelling child migrants?

While this makes for a very problematic analogy, one could note that a child who is brought into the United States illegally would be like a child implanted in a woman (or girl) by rape. That is, their presence is the result of an illegal act and is against the will of the host. While expelling a fetus would certainly (given current technology) result in death, expelling a migrant child generally results in harm and can result, indirectly, in death. As such, if abortion is wrong for the above reasons, then expelling migrant children would be wrong, even if they were brought into the United States illegally.

There are a few obvious ways to counter this reasoning. One is to focus on the distinction between expelling a fetus and expelling a migrant child. As noted above, the fetus will certainly die during an abortion, but expelling a migrant child back into danger does cause certain death. This requires taking the moral position that only certain death matters. Interestingly, if artificial wombs became available, then abortion opponents who take the only death matters view would have to accept that a woman would have every right to expel a fetus into an artificial womb, if death was not certain. That is, if the odds of the fetus would be comparable to the odds of a child being expelled back into a dangerous region.

A second difference is that migrant children are already born, so they are not unborn children. Those who are anti-abortion are often unconcerned about what happens to born children and mothers (anti-abortion states tend to have the highest infant mortality rates), so it would be “consistent” for them to not be concerned about the fate of migrant children. This requires accepting the moral view that what matters is preventing abortion and that once birth occurs, moral concern ends. While not an impossible view, it does seem rather difficult to defend in a consistent manner. As such, those who oppose abortion in all cases would need to accept that expelling migrant children into danger would be morally wrong and they should oppose this with the same vehemence with which they oppose abortion. But what about anti-abortion folks who allow abortion in the case of rape and incest?

Those who oppose abortion but make exceptions for cases of rape and incest would seem to be able to consistently advocate expelling migrant children, even when doing so would put them in danger. This is because they hold to what seems to be a consistent principle: if a child is present against the will of the property owner and as the result of a crime, then the child can be expelled even if this results in death whether this is an abortion or expelling a child who is an illegal migrant. But if the child is present due to consensual activity, then it would be wrong to expel the child.

While sexual consent can be a thorny issue, migration consent is even more problematic. After all, there is the question about what counts as consensual migration. On the face of it, one could simply go with the legal view: those who cross the border illegally are here without consent and can be expelled. But there is the fact that American business and others actively invite migrants to cross the border and want them here, thus seeming to grant a form of consent. Also, people can (or could) legally cross the border to seek asylum, thus there is legal consent for such people, which includes migrant children. So, the matter is less clear cut. But even if we stick with strict legality, then asylum seekers are still here with consent and hence expelling their children is morally like abortion: children are being harmed by being expelled. As such, those who hold an anti-abortion position are obligated to also oppose expelling migrant children if they arrived seeking asylum.

It is worth noting that if the analogy holds, it will also seem to hold in reverse. That is, a person who is opposed to expelling migrant children because of the harm it would do to them would seem to also need to oppose abortion. Pro-choice pro-migrant folks do have a way to get out of this. They can argue that while migrant children are clearly people and hence have that moral status, a developing fetus does not have that moral status and hence the choice of the woman trumps the rights (if any) of the fetus. This is a consistent position since the pro-choice pro-migrant person holds that people have rights, but that the fetus is not a person. In contrast, the anti-abortion anti-migrant person is in something of a bind; they need to argue that unborn fetuses have a greater moral status than already born migrant children. But they are usually comfortable with claiming that an unborn fetus has the same or more rights than the mother, so this is probably not a problem for them.

One the face of it, it is reasonable to think a mass shooter must have “something wrong” with them. Well-adjusted, moral people do not engage in mass murder. But are mass shooters mentally ill? The nature of mental illness is a medical matter, not a matter for common sense pop psychology or philosophers to resolve. But critical thinking can be applied to the claim that mass shootings are caused by mental illness.

One the face of it, it is reasonable to think a mass shooter must have “something wrong” with them. Well-adjusted, moral people do not engage in mass murder. But are mass shooters mentally ill? The nature of mental illness is a medical matter, not a matter for common sense pop psychology or philosophers to resolve. But critical thinking can be applied to the claim that mass shootings are caused by mental illness.

My name is Dr. Michael LaBossiere, and I am reaching out to you on behalf of the CyberPolicy Institute at Florida A&M University (FAMU). Our team of professors, who are fellows with the Institute, have developed a short survey aimed at gathering insights from professionals like yourself in the IT and healthcare sectors regarding healthcare cybersecurity.

My name is Dr. Michael LaBossiere, and I am reaching out to you on behalf of the CyberPolicy Institute at Florida A&M University (FAMU). Our team of professors, who are fellows with the Institute, have developed a short survey aimed at gathering insights from professionals like yourself in the IT and healthcare sectors regarding healthcare cybersecurity. Politicians recognize the political value of mass shootings, with Republicans trying their best to prevent Democrats using these events to pass gun control laws. When a mass shooting occurs, two standard Republican tactics are to assert that it is not time to talk about gun control and to accuse Democrats of trying to score political points. I will consider each of these in turn.

Politicians recognize the political value of mass shootings, with Republicans trying their best to prevent Democrats using these events to pass gun control laws. When a mass shooting occurs, two standard Republican tactics are to assert that it is not time to talk about gun control and to accuse Democrats of trying to score political points. I will consider each of these in turn. When a mass shooting occurs, Republican politicians blame mental illness or

When a mass shooting occurs, Republican politicians blame mental illness or

In the previous essay I drew an analogy between the ethics of abortion and the ethics of migration. In this essay, I will develop the analogy more and do so with a focus on the logic of the analogy. Because everyone loves logic.

In the previous essay I drew an analogy between the ethics of abortion and the ethics of migration. In this essay, I will develop the analogy more and do so with a focus on the logic of the analogy. Because everyone loves logic. As J.S. Mill pointed out in his writing on liberty, people usually do not follow consistent principles. Instead, they act based on likes and dislikes, which often arise from misinformation and disinformation. Comparing the view of many Republicans on abortion to their view of on immigration illustrates this clearly.

As J.S. Mill pointed out in his writing on liberty, people usually do not follow consistent principles. Instead, they act based on likes and dislikes, which often arise from misinformation and disinformation. Comparing the view of many Republicans on abortion to their view of on immigration illustrates this clearly. The

The  While the United States purports to be a democratic republic, it is

While the United States purports to be a democratic republic, it is  One of the founding myths of the United States is that religious liberty is enshrined because people fled to the colonies to escape religious persecution and the strong connections between the church and state in Europe. Whatever the truth of the matter, these are two excellent reasons to legally protect religious liberty. After all, persecuting people based on their faith (or lack thereof) seems wrong. Concentrating secular and theological power has often proven dangerous, although the church and the state can be quite harmful operating on their own. See, for example, Pol Pot or the scandals of the Catholic Church. As such, freedom of religion seems generally good, albeit within limits.

One of the founding myths of the United States is that religious liberty is enshrined because people fled to the colonies to escape religious persecution and the strong connections between the church and state in Europe. Whatever the truth of the matter, these are two excellent reasons to legally protect religious liberty. After all, persecuting people based on their faith (or lack thereof) seems wrong. Concentrating secular and theological power has often proven dangerous, although the church and the state can be quite harmful operating on their own. See, for example, Pol Pot or the scandals of the Catholic Church. As such, freedom of religion seems generally good, albeit within limits.