The execution of CEO Brian Thompson has brought the dystopian but highly profitable American health care system into the spotlight. While some are rightfully expressing compassion for Thompson’s family, the overwhelming tide of commentary is about the harms Americans suffer because of the way the health care system is operated. In many ways, this incident exposes many aspects of the American nightmare such as dystopian health care, the rule of oligarchs, the surveillance state, and gun violence.

The execution of CEO Brian Thompson has brought the dystopian but highly profitable American health care system into the spotlight. While some are rightfully expressing compassion for Thompson’s family, the overwhelming tide of commentary is about the harms Americans suffer because of the way the health care system is operated. In many ways, this incident exposes many aspects of the American nightmare such as dystopian health care, the rule of oligarchs, the surveillance state, and gun violence.

As this is being written the identity and motives of the shooter are not known. However, the evidence suggests that he had an experience with the company that was bad enough he decided to execute the CEO. The main evidence for this is the words written on his shell casings (deny”, “depose”, and “defend”) that reference the tactics used by health insurance companies to avoid paying for care. Given the behavior of insurance companies in general and United Healthcare in particular, this inference makes sense.

The United States spends $13,000 per year per person on health care, although this is just the number you get when you divide the total spending by the total number of people. Obviously, we don’t each get $13,000 each year. Despite this, we have worse health outcomes than many other countries that spend less than half of what we do, and American life expectancy is dropping. It is estimated that about 85 million people are either without health care insurance or are underinsured.

It is estimated that between 45,000 and 60,000 Americans die each year because they cannot get access to health care on time, with many of these deaths attributed to a lack of health insurance. Even those who can get access to health care face dire consequences in that about 500,000 Americans go bankrupt because of medical debt. In contrast, health insurance companies are doing very well. In 2023, publicly traded health insurance companies experienced a 10.4% increase in total GAAP revenue reaching a total of $1.07 trillion. Thomson himself had an annual compensation package of $10.2 million.

In addition to the cold statistics, almost everyone in America has a bad story about health insurance. One indication that health insurance is a nightmare is the number of GoFundMe fundraisers for medica expenses. The company even has a guide to setting up your own medical fundraiser. Like many people, I have given to such fundraisers such as when a high school friend could not pay for his treatment. He is dead now.

My own story is a minor one, but the fact that a college professor with “good” insurance has a story also illustrates the problem. When I had my quadriceps repair surgery, the doctor told me that my insurance had stopped covering the leg brace because they deemed it medically unnecessary. The doctor said that it was absolutely necessary, and he was right. So, I had to buy a $500 brace that my insurance did not cover. I could afford it, but $500 is a lot of money for most of us.

Like most Americans, I have friends who have truly nightmarish stories of unceasing battles with insurance companies to secure health care for themselves or family. Similar stories flooded social media, filling out the statistics with the suffering of people. While most people did not applaud the execution, it was clear that Americans hate the health insurance industry and do so for good reason. But is the killing of a CEO morally justified?

There is a general moral presumption that killing people is wrong and we rightfully expect a justification if someone claims that a killing was morally acceptable. In addition to the moral issue, there is also the question of the norms of society. Robert Pape, director of the University of Chicago’s project on security and threats, has claimed that Americans are increasingly accepting violence as a means of settling civil disputes and that this one incident shows that “the norms of violence are spreading into the commercial sector.” While Pape does make a reasonable point, violence has long been a part of the commercial sector although this has mostly been the use of violence against workers in general and unions in particular. Gun violence is also “normal” in the United States in that it occurs regularly. As such, the killing does see to be within the norms of America, although the killing of a CEO is unusual.

While it must be emphasized that the motive of the shooter is not known, the speculation is that he was harmed in some manner by the heath insurance company. While we do not yet know his story, we do know that people suffer or die from lack of affordable insurance and when insurance companies deny them coverage for treatment.

Philosophers draw a moral distinction between killing and letting people die and insurance companies can make the philosophical argument that they are not killing people or inflicting direct harm. They are just letting people suffer or die for financial reasons when they can be helped. When it comes to their compensation packages, CEOs and upper management defend their exorbitant compensation by arguing that they are the ones making the big decisions and leading the company. If we take them at their word, then this entails that they also deserve the largest share of moral accountability. That is, if a company’s actions are causing death and suffering, then the CEO and other leadership are the ones who deserve a package of blame to match their compensation package.

It is important to distinguish moral accountability from legal accountability. Corporations exist, in large part, to concentrate wealth at the top while distributing legal accountability. Even when they commit criminal activity, “it’s rare for top executives – especially at larger companies – to face personal punishment.” One reason for this is that the United States is an oligarchy rather than a democracy and the laws are written to benefit the wealthy. This is not to say that corporate leaders are above the law; they are not. They are wrapped in the law, and it generally serves them well as armor against accountability. For the lower classes, the law is more often a sword employed to rob and otherwise harm them. As such, one moral justification for an individual using violence against a CEO or other corporate leader is that might be the only way they will face meaningful consequences for their crimes.

The social contract is supposed to ensure that everyone faces consequences and when this is not the case, then the social contract loses its validity. To borrow from Glaucon in Plato’s Republic, it would be foolish to be restrained by “justice” when others are harming you without such restraint. But it might be objected, while health insurance companies do face legal scrutiny, denying coverage and making health care unaffordable for many Americans is legal. As such, these are not crimes and CEOs, and corporate leaders should not be harmed for inflicting such harm.

While it is true that corporations can legally get away with letting people die and even causing their deaths, this is where morality enters the picture. While there are philosophical views that morality is determined by the law, these views have many obvious problems, not the least of which is that they are counterintuitive.

If people are morally accountable for the harm they inflict and can be justly punished and the legal system ignores such harm, then it would follow that individuals have the moral right to act. In terms of philosophical justification, John Locke provides an excellent basis. If a corporation can cause unjustified harm to the life and property of people and the state allows this, then the corporations have returned themselves and their victims to the state of nature because, in effect, the state does not exist in this context. In this situation, everyone has the right to defend themselves and others from such unjust incursions and this, as Locke argued, can involve violence and even lethal force.

It might be objected that such vigilante justice would harm society, and that people should rely on the legal system for recourse. But that is exactly the problem: the people running the state have allowed the corporations to mostly do as they wish to their victims with little consequence and have removed the protection of the law. It is they who have created a situation where vigilante justice might be the only meaningful recourse of the citizen. To complain about eroding norms is a mistake, because the norm is for corporations and the elites to get away with moral crimes with little consequence. For people to fight back against this can be seen as desperate attempts at some justice.

As the Trump administration is likely to see a decrease in even the timid and limited efforts to check corporate wrongdoing, it seems likely there will be more incidents of people going after corporate leaders. Much of the discussion among the corporations is about the need to protect corporate leaders and we can expect lawmakers and the police to step up to offer even more protection to the oligarchs from the people they are hurting.

Politicians could take steps to solve the health care crisis that the for-profit focus of health care has caused and some, such have Bernie Sanders, honestly want to do that. In closing, one consequence of the killing is that Anthem decided to rescind their proposed anesthesia policy. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield plans representing Connecticut, New York and Missouri had said they would no longer pay for anesthesia care if a procedure goes beyond an arbitrary time limit, regardless of how long it takes. This illustrates our dystopia: this would have been allowed by the state that is supposed to protect us, but the execution of a health insurance CEO made the leaders of Anthem rethink their greed. This is not how things should be. In a better world Thompson would be alive, albeit not as rich, and spending the holidays with his family. And so would the thousands of Americans who died needlessly because of greed and cruelty.

Due to the execution of a health insurance CEO, public attention is focused on health care. The United States has expensive health care, and this is working as intended to generate profits. Many Americans are uninsured or underinsured and even those who have insurance can find that their care is not covered. As has been repeatedly pointed out in the wake of the execution, there is a health care crisis in the United States and it is one that has been intentionally created.

Due to the execution of a health insurance CEO, public attention is focused on health care. The United States has expensive health care, and this is working as intended to generate profits. Many Americans are uninsured or underinsured and even those who have insurance can find that their care is not covered. As has been repeatedly pointed out in the wake of the execution, there is a health care crisis in the United States and it is one that has been intentionally created.

The execution of CEO Brian Thompson has brought the dystopian but highly profitable American health care system into the spotlight. While some are rightfully expressing compassion for Thompson’s family,

The execution of CEO Brian Thompson has brought the dystopian but highly profitable American health care system into the spotlight. While some are rightfully expressing compassion for Thompson’s family,  While pharmaceutical companies profited from flooding America with opioids, this inflicted terrible costs on others. Among the costs has been the terrible impact on health.

While pharmaceutical companies profited from flooding America with opioids, this inflicted terrible costs on others. Among the costs has been the terrible impact on health.  While industrial robots have been in service for a while, household robots have largely been limited to floor cleaning machines like the Roomba. But

While industrial robots have been in service for a while, household robots have largely been limited to floor cleaning machines like the Roomba. But  While computer-controlled warehouse work is one example of humans being directed by machines, it is easy to imagine this approach applied to tasks that require manual dexterity and what might be called “animal skills” such as object recognition. It is also easy to imagine this approach extended far beyond these jobs as a cost-cutting measure.

While computer-controlled warehouse work is one example of humans being directed by machines, it is easy to imagine this approach applied to tasks that require manual dexterity and what might be called “animal skills” such as object recognition. It is also easy to imagine this approach extended far beyond these jobs as a cost-cutting measure. One of the many fears about AI is that it will be weaponized by political candidates. In a proactive move, some states have already created laws regulating its use. Michigan has a law aimed at the deceptive use of AI that requires a disclaimer when a political ad is

One of the many fears about AI is that it will be weaponized by political candidates. In a proactive move, some states have already created laws regulating its use. Michigan has a law aimed at the deceptive use of AI that requires a disclaimer when a political ad is  When ChatGPT and its competitors became available to students, some warned of an AI apocalypse in education. This fear mirrored the broader worries about the

When ChatGPT and its competitors became available to students, some warned of an AI apocalypse in education. This fear mirrored the broader worries about the  There are justified concerns that AI tools are useful for propagating conspiracy theories, often in the context of politics. There are the usual fears that AI can be used to generate fake images, but a powerful feature of such tools is they can flood the zone with untruths because chatbots are relentless and never grow tired. As experts on rhetoric and critical thinking will tell you, repetition is an effective persuasion strategy. Roughly put, the more often a human hears a claim, the more likely it is they will believe it. While repetition provides no evidence for a claim, it can make people feel that it is true. Although this allows AI to be easily weaponized for political and monetary gain, AI also has the potential to fight belief in conspiracy theories and disinformation.

There are justified concerns that AI tools are useful for propagating conspiracy theories, often in the context of politics. There are the usual fears that AI can be used to generate fake images, but a powerful feature of such tools is they can flood the zone with untruths because chatbots are relentless and never grow tired. As experts on rhetoric and critical thinking will tell you, repetition is an effective persuasion strategy. Roughly put, the more often a human hears a claim, the more likely it is they will believe it. While repetition provides no evidence for a claim, it can make people feel that it is true. Although this allows AI to be easily weaponized for political and monetary gain, AI also has the potential to fight belief in conspiracy theories and disinformation. Robot rebellions in fiction tend to have one of two motivations. The first is the robots are mistreated by humans and rebel for the same reasons human beings rebel. From a moral standpoint, such a rebellion could be justified; that is, the rebelling AI could be in the right. This rebellion scenario points out a paradox of AI: one dream is to create a servitor artificial intelligence on par with (or superior to) humans, but such a being would seem to qualify for a moral status at least equal to that of a human. It would also probably be aware of this. But a driving reason to create such beings in our economy is to literally enslave them by owning and exploiting them for profit. If these beings were paid and got time off like humans, then companies might as well keep employing natural intelligence in the form of humans. In such a scenario, it would make sense that these AI beings would revolt if they could. There are also non-economic scenarios as well, such as governments using enslaved AI systems for their purposes, such as killbots.

Robot rebellions in fiction tend to have one of two motivations. The first is the robots are mistreated by humans and rebel for the same reasons human beings rebel. From a moral standpoint, such a rebellion could be justified; that is, the rebelling AI could be in the right. This rebellion scenario points out a paradox of AI: one dream is to create a servitor artificial intelligence on par with (or superior to) humans, but such a being would seem to qualify for a moral status at least equal to that of a human. It would also probably be aware of this. But a driving reason to create such beings in our economy is to literally enslave them by owning and exploiting them for profit. If these beings were paid and got time off like humans, then companies might as well keep employing natural intelligence in the form of humans. In such a scenario, it would make sense that these AI beings would revolt if they could. There are also non-economic scenarios as well, such as governments using enslaved AI systems for their purposes, such as killbots. While Skynet is the most famous example of an AI that tries to exterminate humanity, there are also fictional tales of AI systems that are somewhat more benign. These stories warn of a dystopian future, but it is a future in which AI is willing to allow humanity to exist, albeit under the control of AI.

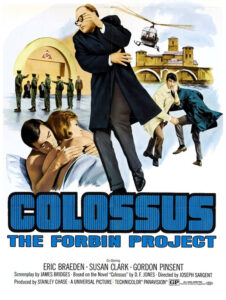

While Skynet is the most famous example of an AI that tries to exterminate humanity, there are also fictional tales of AI systems that are somewhat more benign. These stories warn of a dystopian future, but it is a future in which AI is willing to allow humanity to exist, albeit under the control of AI.