This contains many spoilers. When I first saw the trailer for The Tomorrow War my thought was “I wonder who that discount Chris Pratt is?” When I realized it was the actual Chris Pratt, my thought was “he must really need money.” Yes, it is exactly that kind of movie. I will start with some non-philosophical complaints and then move on to what is most interesting (and disappointing) about the flick: time travel.

This contains many spoilers. When I first saw the trailer for The Tomorrow War my thought was “I wonder who that discount Chris Pratt is?” When I realized it was the actual Chris Pratt, my thought was “he must really need money.” Yes, it is exactly that kind of movie. I will start with some non-philosophical complaints and then move on to what is most interesting (and disappointing) about the flick: time travel.

Like many war movies of its ilk, this flick handles armored fighting vehicles by leaving them out. Instead, the human forces confront the aliens with infantry, Humvees, transport helicopters, and fighter-bombers. Oddly, the infantry is armed with standard guns that are largely ineffective against the aliens. This is even though they know this and there are plenty of existing infantry weapons that would kill the aliens. No armored fighting vehicles (like tanks) are used, and Humvees are the mainstay of the forces. They get easily destroyed by the aliens charging into them like deranged moose (except when the main characters are in one). Maybe leaving out armored vehicles is a budget issue, but it mainly seems because the aliens, which are basically animals, would be slaughtered by modern armor. They could do no damage, and antivehicle weapons would slaughter them. My theory is that rather than come up with an alien that could beat armor, the writers just leave out armored vehicles. The transport helicopters, as one would expect in such a film, generally fly within the leaping range of the aliens and attack helicopters do not exist (they do have armed drones, though). The fighter-bombers exist, as always, as a stupid plot device: in one part of the movie the hero is tasked with rescuing research that is the last hope for victory, yet an air strike is called on the otherwise empty city and it cannot be called off. But enough of that, on to the time travel.

Time travel is always a mess in philosophy, science, and fiction. But it can be fun if used properly. The movie does have an interesting, though unoriginal, premise: humans in the future have built a time machine and are using it to recruit soldiers and supplies from the past to fight the aliens that have killed all but 500,000 people. As movies must, the movie puts limits on time travel. The biggest limitation is that the time “tunnel” has a fixed temporal range of 30 years. When people go forward, they go forward thirty years. When they go back, they go back thirty years. One of the minor characters explains it in terms of two connected rafts in a river: they always stay the same distance apart but move along with the river. One of the supporting characters asks the obvious question as to why they do not make more rafts. The answer is that the time machine they have is held together with bubble gum and chicken wire, so they cannot build another one. While not the worst answer a writer could come up with, it is stupid within the rules of the movie: people and equipment can move freely between the present and future. More time machines could be made in the past and brought to the future. They could even build a time machine in the present and open a time tunnel to 30 years earlier, giving humanity another 30 years of preparation time. And then do that repeatedly until the paradoxes destroy reality. A better answer would have been some techno-metaphysical babble about how the time stream can only permit one time tunnel to operate. But let us get back to the fact that people and things can move between the times.

At one critical point in the movie, the heroes have completed a toxin that will kill the female aliens. But just as they complete it, their last base is overrun, and Chris Pratt is recalled to the past, with the toxin. The time machine is done, so the war has been lost. Apparently having struck his head in the fall, Pratt thinks he has no way of getting the toxin to the future, so everything is lost. The nations of the world also just sort of decide to give up as well, which would make sense if everyone believed in metaphysical determinism. Pratt’s character apparently lost the ability to understand how time works: the toxin he has in the present will eventually reach the future. It will just travel one day at a time towards that future.

Going back to the raft analogy, the time machine is like a pneumatic tube that has a fixed length, it can quickly move things back and forth over that distance. But, and here is how normal time works, one can also walk an object to towards the other end of the tube in the future. As such, when the aliens show up, the humans will have as much toxin as they wish to make to use against them. This feature of time would also allow the humans to plan their missions very effectively. To illustrate, I will use a smaller version of the time tunnel thing.

Suppose that on 12/5/2026 I build a time tunnel that reaches back 1 year (roughly). On that day, the tunnel pops open on 12/5/2025 and Mike 2026 can hand Mike 2025 a usb drive full of useful information (such as winning lottery numbers, weather reports, news reports on disasters, and so on). How would this be possible? Here is how. When Mike 2026 arrives, he tells Mike 2025 to fill up the drive. Mike 2025 spends the year doing just that, so in 2026 the drive is full of information and Mike 2026 hands it to Mike 2025 when he arrives. Mike 2025 can now use all that information.

In the case of the movie, when the time tunnel opens for the first time, they could do the same thing: as people come from the future, they just update information. Thirty years after the time tunnel opens, the travelers have all that information and can use it to change missions that failed, and so on, thus changing the future. This, of course, creates the usual time travel mess of changing the future based on information from the future. An analogous problem also arises from bringing objects back from the future that depend on the future to exist. I will use the toxin from the movie to illustrate this old problem.

As mentioned above, Pratt’s character helps create a toxin in the future and brings it back to the past. He is weirdly baffled about how he will get it to the future but decides to not give up the fight. With the help of some others, he manages to determine that the aliens landed long ago and were frozen in the ice (like in the Thing). So, he does the sensible thing: he goes to a government official and tells him he knows where the aliens are and has the toxin to kill them. So, the official does the usual movie thing: he just refuses. So, Pratt and his associates do the usual movie thing and go it on their own. They use the toxin to kill a couple aliens, then blow up the alien ship (so they did not need the toxin). Then Pratt and his dad beat up the female that escapes the ship. The movie ends with everyone being happy. Except, obviously, the aliens and anyone who might have wanted the technology in that ship. Because of this, the tomorrow war never occurs. Which leads to some problems, but I will focus on the toxin.

The toxin only exists because it was created in the future in response to the aliens. To steal from Aquinas who stole from Aristotle, “To take away the cause is to take away the effect.” As such, the defeat of the aliens would mean that the toxin would never exist, it could not be there in the past. Also, going back to the information problem, Pratt only knows about the aliens because of the tomorrow war, which he prevented from happening. They could, of course, have done a “Yesterday’s Enterprise” thing: the whole timeline changes or something. This is just one of the many paradoxes of time travel.

Another approach, which one could mentally write into the movie if one wishes, is that time travel is dimensional travel or creates time-line branches (which is effectively dimensional travel). So, the future Pratt goes to is real and does not change for it is what it is. When he comes back from that future (alternative reality) with the toxin and kills the aliens in his present, this creates a new future timeline for him. This means, of course, that his alternative adult daughter dies in that alternative future, but his new alternative daughter does not, since the war does not happen in the new timeline.

The movie, I think, would have a been a bit more interesting if they used the alternative timeline approach and they could have had a brief moral debate about obligations to help in an alternate future of one’s own reality. Or it could be a plot twist that the people doing the “time travel” knew they were going to another reality but decided to lie about it to get help.

In terms of the quality of the movie as a movie; well, it is what one would expect from either a store-brand Chris Pratt or a name-brand Chris Pratt who really just needs the money.

Some years ago, the right made

Some years ago, the right made  A few years ago, the estate of Dr. Seuss decided to pull six books from publication because the works include

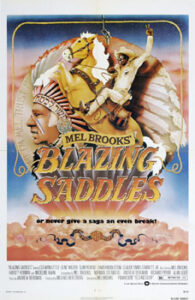

A few years ago, the estate of Dr. Seuss decided to pull six books from publication because the works include  Back when Black Lives Mattered, (HBO) Max briefly pulled ‘Gone with the Wind’ from its video library as an indirect response to protests about racism.

Back when Black Lives Mattered, (HBO) Max briefly pulled ‘Gone with the Wind’ from its video library as an indirect response to protests about racism.  As noted in previous essays, Wizards of the Coast (WotC) created a stir when they posted an article on

As noted in previous essays, Wizards of the Coast (WotC) created a stir when they posted an article on  When the culture war opened a gaming front, I began to see racist posts in gaming groups on Facebook and other social media. Seeing these posts, I wondered whether they are made by gamers who are racists, racists who game or merely trolls (internet, not D&D).

When the culture war opened a gaming front, I began to see racist posts in gaming groups on Facebook and other social media. Seeing these posts, I wondered whether they are made by gamers who are racists, racists who game or merely trolls (internet, not D&D). A few years ago the owners of D&D, Wizards of the Coast,

A few years ago the owners of D&D, Wizards of the Coast,  A few years ago, Wizards of the Coast(WotC), who own Dungeons & Dragons,

A few years ago, Wizards of the Coast(WotC), who own Dungeons & Dragons,  Artists often claim to have a special relationship that gives them rights over their art even after it has been sold. One example involved artist David Phillips and Fidelity. Fidelity hired Phillips to create a sculpture park and then the company wanted to make changes to it. With neither side willing to compromise, Phillips sued Fidelity alleging the changes would mutilate his work. A famous example occurred in 1958 when the owner of the mobile Pittsburgh donated it to Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County. Alexander Calder, the creator of the mobile, unsuccessfully opposed the plan to repaint the black and white mobile green and gold. In 1969 sculptor Takis (Panayotis Vassilakis) tried to remove his work from New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. He claimed he had the right to determine how his art was exhibited—even after it had been sold. A more recent example involves watches.

Artists often claim to have a special relationship that gives them rights over their art even after it has been sold. One example involved artist David Phillips and Fidelity. Fidelity hired Phillips to create a sculpture park and then the company wanted to make changes to it. With neither side willing to compromise, Phillips sued Fidelity alleging the changes would mutilate his work. A famous example occurred in 1958 when the owner of the mobile Pittsburgh donated it to Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County. Alexander Calder, the creator of the mobile, unsuccessfully opposed the plan to repaint the black and white mobile green and gold. In 1969 sculptor Takis (Panayotis Vassilakis) tried to remove his work from New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. He claimed he had the right to determine how his art was exhibited—even after it had been sold. A more recent example involves watches.