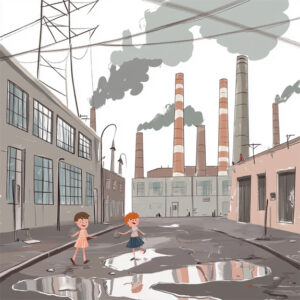

When it comes to pollution, people respond with a cry of NIMBY and let loose the dogs of influence. This shows that everyone gets what is obviously true: pollution is unsightly, unpleasant, and unhealthy. Air pollution alone is deadly, killing millions of us each year. It is also obviously true that our civilizations flood our home with pollution, and we must decide where this pollution goes.

When it comes to pollution, people respond with a cry of NIMBY and let loose the dogs of influence. This shows that everyone gets what is obviously true: pollution is unsightly, unpleasant, and unhealthy. Air pollution alone is deadly, killing millions of us each year. It is also obviously true that our civilizations flood our home with pollution, and we must decide where this pollution goes.

As one would expect, the cost of pollution is regularly shifted onto those with less influence. The wealthy and politically influential use this power to ensure that pollution is concentrated in places where the poor and uninfluential live. To illustrate, we do not see incinerators or coal burning power plants constructed near the residences of Nancy Pelosi, Ted Cruz, Bill Gates, or Oprah.

In the United States (and elsewhere) race is also a factor: pollution is concentrated along racial lines, even accounting for disparities of income. To illustrate, highways tend to run through minority neighborhoods and industrial plants tend to be located near minority residences. While some might rush to point out that white Americans are also subject to horrific levels of pollution, this is hardly the devasting riposte that one might think it is. After all, pollution is distributed disproportionally to wealth and there are many poor white people in America. Also, pointing out that white people are also heavily exposed to pollution only shows how widespread the problem is. As with most harms in America, pollution hurts the poor, the children, and minorities the most.

In some cases, sources of pollution are intentionally inflicted on the poor and minorities. In other cases, the same result arises without conscious intention. To illustrate, if a company proposed to build a refinery near a wealthy white neighborhood, the residents would use their influence to block it. The company would keep trying to find a location and would, of course, end up somewhere where the inhabitants lacked the power to prevent it from being built in their backyard. This would be a poorer area that is also likely also to have a minority population. It can be argued that the wealthy white folks have no desire to inflict pollution on these poor people, it just happens because of the disparity in power. After all, that refinery must go somewhere, just not in their backyard. While the folks who make the decisions probably care little about ethical theory, it can and should be applied to this decision making, be it direct or indirect.

One obvious approach to such large-scale moral decision making is to use a form of utilitarianism: the pollution should be located where it does the least harm to those who matter morally. Deciding who (and what) matters and how much they matter involves sorting out the scope of morality. There is also the problem of sorting out the calculation of value: what is the measure of the good and the evil? There are many ways to address matters of scope and value, which can lead to good faith moral debate. Interestingly, a solid argument can be made for the common practice of dumping the most pollution on those with the least power.

As John Kenneth Galbraith said, “The modern conservative is engaged in one of man’s oldest exercises in moral philosophy; that is, the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness.” Utilitarianism provides an easy way to do just that by adjusting the scope of morality. As noted above, determining the scope of morality is a matter of determining who has moral worth and to what degree they have it. One extreme example is ethical egoism. On this consequentialist view, each person limits the scope of morality to themselves. Ayn Rand is a good example of an ethical egoist. On her view, everyone should be selfish and do what maximizes their self-interest. In terms of the scope of morality, the ethical egoist sees themself as the only one with moral worth. The opposing view is altruism. This is the view that at least some other people count morally.

An ethical egoist can easily provide a moral justification for shifting the cost of pollution onto others: only they count, so the right thing to do is to ensure that someone else is exposed to pollution. Obviously enough, this view entails that everyone will be selfishly striving to push the pollution onto someone else and they are all morally right to do so. The matter would, from a practical standpoint, be settled by strength: the strong will do as they wish, the weaker will suffer as they must. This is likely to strike some as being fundamentally unethical or even an absence of ethics. But one can expand the scope of morality while still pushing pollution onto others.

One obvious approach is to argue that the people in the upper classes have more moral worth than those in the lower classes. How the scope is set can vary greatly. One might, for example, claim that only the elites have any moral worth at all. One could be more “generous” and grant all classes moral status, but have the moral status correspond to the class status. On this sort of view, the poor would have some moral worth, but they would matter far less morally than the elites. This seems to be a commonly held view: only the most heartless would claim that the poor have no value, but our civilizations treat the lower classes as having far less moral worth. They are generally less honest about this these days; but it is evident upon even a cursory examination of countries like the United States and China.

One can also bring race in as a factor in setting the scope of morality. The United States provides a clear example of this: while many racists would accept that people outside of their group have some moral worth, a racist regards their group as having greater moral worth than others. This allows an easy “justification” of shifting the harms of pollution onto minorities: for the racist, these people have less worth and thus it makes moral sense to have them suffer the harms. There are utilitarians, such as J.S. Mill, who have a broader scope of morality, taking all humans and even much of “sentient creation” to count morally.

For those who consider all people to have moral worth, then shifting pollution onto the poor and onto minorities becomes more morally difficult. One could still make a case for doing so, but it would be harder than simply adjusting the scope of morality to devalue the poor and minorities.

During the last pandemic, some organizations mandated vaccination against COVID-19. As another pandemic is inevitable, it is worth revisiting the moral issue of mandatory vaccination in response to a pandemic.

During the last pandemic, some organizations mandated vaccination against COVID-19. As another pandemic is inevitable, it is worth revisiting the moral issue of mandatory vaccination in response to a pandemic.

While most states have hate crime statutes

While most states have hate crime statutes It might seem like woke madness to claim that medical devices can be biased

It might seem like woke madness to claim that medical devices can be biased A few years ago, PragerU tried to push back on Twitter (now X) against arguments by young Americans about racism. In general, getting involved in social media battles is a bad idea. To use an AD&D analogy, these fights are like punching green slime: the more you attack, the more you hurt yourself. And you end up covered in slime. It is usually best to avoid rather than engage.

A few years ago, PragerU tried to push back on Twitter (now X) against arguments by young Americans about racism. In general, getting involved in social media battles is a bad idea. To use an AD&D analogy, these fights are like punching green slime: the more you attack, the more you hurt yourself. And you end up covered in slime. It is usually best to avoid rather than engage.  In addition to the pandemic, 2020 was marked by

In addition to the pandemic, 2020 was marked by  This contains many spoilers. When I first saw the trailer for The Tomorrow War my thought was “I wonder who that discount Chris Pratt is?” When I realized it was the actual Chris Pratt, my thought was “he must really need money.” Yes, it is exactly that kind of movie. I will start with some non-philosophical complaints and then move on to what is most interesting (and disappointing) about the flick: time travel.

This contains many spoilers. When I first saw the trailer for The Tomorrow War my thought was “I wonder who that discount Chris Pratt is?” When I realized it was the actual Chris Pratt, my thought was “he must really need money.” Yes, it is exactly that kind of movie. I will start with some non-philosophical complaints and then move on to what is most interesting (and disappointing) about the flick: time travel. In the face of real problems, the Republican legislature of my adopted state of Florida has been busy addressing fictional problems and undermining democracy. For example,

In the face of real problems, the Republican legislature of my adopted state of Florida has been busy addressing fictional problems and undermining democracy. For example,  As a runner, I have often imagined what it would be like to have super speed like the Flash or Quicksilver. Unfortunately for my super speed dreams, Kyle Hill has presented the

As a runner, I have often imagined what it would be like to have super speed like the Flash or Quicksilver. Unfortunately for my super speed dreams, Kyle Hill has presented the