When the COVID-19 virus invaded the United States, it found an ill-prepared and complacent foe. As such, the impact proved devastating. One clear lesson is that the aggressively for-profit health care system is a weak point in our national defense against disease. I will make my case with the obvious analogy between health care and military defense.

When the COVID-19 virus invaded the United States, it found an ill-prepared and complacent foe. As such, the impact proved devastating. One clear lesson is that the aggressively for-profit health care system is a weak point in our national defense against disease. I will make my case with the obvious analogy between health care and military defense.

Imagine, if you will, that the United States military operated like our health care system. Our current health care system is analogous to relying on mercenaries, albeit with a professional code of ethics and some loyalty to the nation. During normal times, the health care system is almost entirely mercenary: it fights battles to make a profit. This is not to disparage medical professionals, but the profit model chosen by those who control health care. Because the goal is profit, the health care system is operated to minimize costs and maximize income. This means operating like a mercenary force: employing minimal personnel to do the job, maintaining only necessary resources for normal operations, focusing on the highest paying customers, and only taking on profitable contracts. This is a rational way to operate a mercenary unit. But is it a good way for a national military to run? That is, would it make sense for the United States to switch from a public military to a mercenary military?

Laying aside the usual problems of loyalty and dependability, relying on a mercenary (for-profit) military model would be a problem for the United States. One obvious problem is the United States needs a large force that ready to engage in prolonged conflicts that we do not always get to pick. After all, national security need not match up with what would be the most profitable military operations and requires keeping resources available, such as the reserves, that no purely for-profit military would sensibly maintain. If the United States relied on a mercenary military for its defense, it would face many challenges in times of crisis: rapidly ramping up to meet the challenge, making the operations profitable enough to motivate mercenary forces (such as paying them enough to protect everybody). These are, in fact, all the reasons why a country should have a public, national military rather than relying on mercenaries. After all, the United States needs a military that is ready to face whatever threat arises and not a force limited by the need to make a profit. It is thus no surprise that our mercenary healthcare system runs into analogous problems.

Being focused on profits, the health care system operates with minimum resources and personnel. Maintaining a reserve of medical professionals and the resources needed for a crisis would cut deeply into profits. The government, it should be noted, does keep some medical resources in reserve, but this is obviously the public sector in operation. Because of this razor thin operation that maximizes profits, the health care system is like a mercenary unit: ill-prepared when the battle turns into a full-scale war requiring large reserves and resources. The health care system normally deals with the problem of resources by allocating them based on profit; like a smart mercenary commander who accepts the lucrative contract to fight easier opponents. In the case of health care, the wealthy get the best health care money can buy, while the poor get whatever is left over. But in the case of a national crisis, the response must be large scale: it is an invasion and not just the usual battles. People face the same problem, be it in a battle fought by mercenaries or health care provided by mercenaries: they need to be able to pay in order to get protection.

One principled reason we have a national public military rather than using mercenary forces is that we accept that the military should protect all citizens and not just those who can afford to hire their own mercenary forces. The same principle should apply to health care: having a mercenary medical system means that a citizen’s survival depends on what they can pay, and this is not acceptable. If we believe that the state should protect all citizens equally from ISIS and North Korea, then we should accept that the state should protect all citizens equally from COVID-19 and H1N1.

It could be sensibly argued that the military model fits in the case of pandemics and while health care should be modified to address the threat of pandemics, the for-profit model should remain for everyday medical matters. So, for example, everyone should have access to testing and treatment for COVID-19, but we should still be on our own when it comes to the flu, hepatitis or automobile accidents.

One reply is to argue that the state has obligations in the everyday medical care of the citizens. To use another analogy, if handling pandemics is like fighting a war, lesser threats are analogous to small-scale conflicts or police operations. We do not, for example, expect Americans to pay to get police services to address crimes against them, just because the crime is against them and not a pandemic of crime.

This is not to say that the state must pay for everything. No doubt someone is thinking about the state paying for breast implants or face lifts. But expecting the state to pay for these would be like expecting the state to pay the bill because a citizen wanted to see a military parade on their street. As such, only the medically necessary should be covered. Just as we limit the obligations of the national military and local police, the obligations of health care can also be limited. This can lead to debates about what is necessary, but these disputes can be addressed in good faith.

It could be objected that people bring on their own health problems by bad choices and this should not be the responsibility of the state. But the same argument would apply to the police and military. For example, if the police thought that you did not take enough precautions to protect your car, they could refuse to do anything about it being stolen. Or, as another example, if you get attacked and injured, they could refuse to help you because you failed to take enough karate.

If we continue to rely on mercenary health care as part of our national defense, we can expect things to play out in a manner analogous to relying on mercenary forces for our national defense: no matter how brave or dedicated the individual soldiers are, a mercenary system is simply not up to facing the challenge.

The survival argument for establishing off world colonies has considerable appeal. It begins with a consideration of the threat of extinction. There have been numerous extinction events in the past and there is no reason to think humans are exempt. There are a variety of plausible doomsday scenarios that could cause our extinction, ranging from the classic asteroid strike to the human-made nuclear Armageddon. Less extreme, but still of concern, are disasters that would end our civilization without exterminating us.

The survival argument for establishing off world colonies has considerable appeal. It begins with a consideration of the threat of extinction. There have been numerous extinction events in the past and there is no reason to think humans are exempt. There are a variety of plausible doomsday scenarios that could cause our extinction, ranging from the classic asteroid strike to the human-made nuclear Armageddon. Less extreme, but still of concern, are disasters that would end our civilization without exterminating us. As noted in previous essays, critics of capitalism are often accused of being Marxists and this attack is used to fallaciously justify rejecting their claims. The accusation of Marxism is also used as a signal to certain audiences; it is a way of saying the target is a “bad person” and should be disliked. In most cases the target is not a Marxist as they are rare in the United Sates, even in higher education.

As noted in previous essays, critics of capitalism are often accused of being Marxists and this attack is used to fallaciously justify rejecting their claims. The accusation of Marxism is also used as a signal to certain audiences; it is a way of saying the target is a “bad person” and should be disliked. In most cases the target is not a Marxist as they are rare in the United Sates, even in higher education. As noted in my previous essay, critics of capitalism are often accused of being envious or Marxists. As shown in that essay, even if a critic is envious, it is fallacious to conclude their criticism is therefore wrong. But it could be argued that a person’s envy can bias them and diminish their credibility. I will look at this and examine envy. I will then engage in some self-reflection on whether I am envious.

As noted in my previous essay, critics of capitalism are often accused of being envious or Marxists. As shown in that essay, even if a critic is envious, it is fallacious to conclude their criticism is therefore wrong. But it could be argued that a person’s envy can bias them and diminish their credibility. I will look at this and examine envy. I will then engage in some self-reflection on whether I am envious. I am, on occasion, critical of capitalism. I am, on occasion, accused of being critical because I am allegedly envious or a Marxist. If these were attacks aimed only at me, they would be of no general interest. However, accusing critics of capitalism of being motivated by envy or Marxism is a common tactic that warrants evaluation. I will begin with the accusation of envy.

I am, on occasion, critical of capitalism. I am, on occasion, accused of being critical because I am allegedly envious or a Marxist. If these were attacks aimed only at me, they would be of no general interest. However, accusing critics of capitalism of being motivated by envy or Marxism is a common tactic that warrants evaluation. I will begin with the accusation of envy. Because the United Kingdom was suffering from a shortage of sperm donors it was been proposed that men be allowed to donate their sperm after they are dead

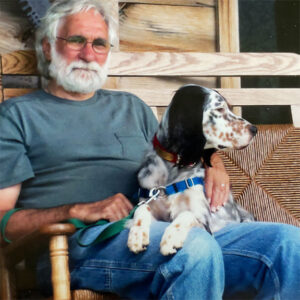

Because the United Kingdom was suffering from a shortage of sperm donors it was been proposed that men be allowed to donate their sperm after they are dead Thank you for being here. You all meant a lot to my dad, and he appreciated your presence in his life.

Thank you for being here. You all meant a lot to my dad, and he appreciated your presence in his life. Prior to Trump’s first victory mainstream Republicans attacked and criticized. His victory not only silenced almost all his conservative critics most became fawning Trump loyalists.

Prior to Trump’s first victory mainstream Republicans attacked and criticized. His victory not only silenced almost all his conservative critics most became fawning Trump loyalists.  James J. LaBossiere, born on December 19, 1939, in Norway, Maine, was the son of Alfred “Cooper” and Gladys Clement LaBossiere. He passed away peacefully on May 3, 2025, leaving behind an enduring legacy as a father and a teacher.

James J. LaBossiere, born on December 19, 1939, in Norway, Maine, was the son of Alfred “Cooper” and Gladys Clement LaBossiere. He passed away peacefully on May 3, 2025, leaving behind an enduring legacy as a father and a teacher.