If you have yet to see the first episode of season one of Disney’s Loki series, this essay contains spoilers. This episode presents some of the metaphysics of the MCU: there are many timelines (alternate realities) and variants of people, such as Loki and Deadpool, exist in some of them.

Loki is, obviously, the main character of Loki. In fact, he is two main characters: the anti-hero Loki and the hero-anti Loki (the villain). Since the metaphysics of the MCU includes time travel, this entails that the same person can be at different places at the same time. They can even fight, as happened with Captain America. While this is a metaphysical mess, this means time travel can be used as a multiplier: a person can time it so different versions of themselves arrive at the same place at the same time. So, for example, Loki could show up to fight an enemy at a set time and arrange for himself to go back or forwards in time ten times and end up with eleven of himself to overwhelm the foe. This, of course, leads to the usual paradoxes and problems of time travel. A future Loki could tell a distant past Loki about things that a middle past Loki did not know, but then the middle past Loki would know it. While this is even more of a mess, the time travelling Lokis could remain there in that time and start their own lives or perhaps travel back to a more distant past over and over to create a vast army of Lokis that meet up at a future time to do whatever it is that his character arc directs him to do.

Such time travel has various other problems. A point often made in time travel tales is the importance of not changing the past. Some sci-fi stories do allow a change in the past to change the future; other stories simply make it so that whatever the time travelers do is what happened anyway. That is, they make no change in the past because what they do is what they did and will always done did (Star Trek IV implies this). The classic grandfather paradox falls into this family of problems: if a person goes back to the past and changes things that impact their ability to go to the past (such as killing their grandfather), then they could not go back to change the past and hence the past would be unchanged and so they could go back to the past. But they could not, because if they made that change then they could not go back. And so on. In fiction, the writers simply write whatever they wish, but this does not address the matter of how this would all “really” work.

There is also the problem of personal identity: in the metaphysics of the MCU variants arise and a new timeline branch could presumably also spawn variants that create additional branches. As there are multiple Lokis in the show, they both spawned off the main timeline. Perhaps one Loki “divided”, or one Loki “split” from the other Loki. Or perhaps there are three (or more) Lokis: there is the Loki who remained on the timeline and was killed by Thanos. There is the Loki who escaped from the Avengers because of their time heist (the anti-hero of the show) and the third Loki who is the villain. Because of time travel, the third Loki might have split from the second Loki in the future. As always, time travel is a mess.

Having multiple Lokis does create the usual problems for personal identity. After all, what provides personal identity is supposed to make a person the person they are, distinct from all other things. As such, it would seem to be something that should not be able to be duplicated. Otherwise, it would not be what makes an entity distinct from all other things. If there are two Lokis in a room, there must be something that makes them two rather than one. There must also be something that makes each of them the Loki they are. But is this true?

One approach is taking inspiration from David Hume’s theory of personal identity. After he argues a person is a bundle of perceptions, he ends up saying that, “The whole of this doctrine leads us to a conclusion, which is of great importance in the present affair, viz. that all the nice and subtle questions concerning personal identity can never possibly be decided, and are to be regarded rather as grammatical than as philosophical difficulties.” While this might be true, it does not satisfy. But it does provide a way of resolving a room full of Lokis: it’s a matter of grammar.

Another approach is trying to sort out the metaphysics of personal identity in the context of time travel. After all, time travel requires that entities can be multiply located while personal identity would seem to forbid duplication of what individuates. The reason time travel requires multiple location is that something from one time travels to another time and the matter or energy that makes up what travels will also be present when it arrives. So, the same thing will be in two places at the same time; something that is not normally possible. But one could accept the existence of metaphysical entities that allow this.

Yet another approach, and one that seems to match how the timelines were presented in the show, is that a branching creates an entire new reality that is similar but not identical to the first. This would also duplicate the people, perhaps creating them ex nihilo. So, the various Lokis would be similar people, but not the same person.

As a philosopher, I annoy people in many ways. One is that I almost always qualify the claims I make. This is not to weasel (weakening a claim to protect it from criticism) but because I am aware of my epistemic limitations: as Socrates said, I know that I know nothing. People often prefer claims made with certainty and see expressions of doubt as signs of weakness. Another way I annoy people is by presenting alternatives to my views and providing reasons as to why they might be right. This has a downside of complicating things and can be confusing. Because of these, people often ask me “what do you really believe!?!” I then annoy the person more by noting what I think is probably true but also insisting I can always be wrong. This is for the obvious reason that I can always be wrong. I also annoy people by adjusting my views based on credible changes in available evidence. This really annoys people: one is supposed to stick to one view and adjust the evidence to suit the belief. The origin story of COVID-19 provides an excellent example for discussing this sort of thing.

As a philosopher, I annoy people in many ways. One is that I almost always qualify the claims I make. This is not to weasel (weakening a claim to protect it from criticism) but because I am aware of my epistemic limitations: as Socrates said, I know that I know nothing. People often prefer claims made with certainty and see expressions of doubt as signs of weakness. Another way I annoy people is by presenting alternatives to my views and providing reasons as to why they might be right. This has a downside of complicating things and can be confusing. Because of these, people often ask me “what do you really believe!?!” I then annoy the person more by noting what I think is probably true but also insisting I can always be wrong. This is for the obvious reason that I can always be wrong. I also annoy people by adjusting my views based on credible changes in available evidence. This really annoys people: one is supposed to stick to one view and adjust the evidence to suit the belief. The origin story of COVID-19 provides an excellent example for discussing this sort of thing. Dice (unloaded) seem a paradigm of chance: when rolling a die, one cannot know the outcome in advance because it is random. For example, if you roll a twenty-sided die, then there is supposed to be an equal chance to get any number. If you roll it 20 times, it would not be surprising if you didn’t roll every number. If you rolled the die 100 times, chance says you would probably roll each number 5 times. But it would not be shocking if this did not occur. But if you rolled a thousand or a million times, then you would expect the results to match the predicted probability closely because you would expect the

Dice (unloaded) seem a paradigm of chance: when rolling a die, one cannot know the outcome in advance because it is random. For example, if you roll a twenty-sided die, then there is supposed to be an equal chance to get any number. If you roll it 20 times, it would not be surprising if you didn’t roll every number. If you rolled the die 100 times, chance says you would probably roll each number 5 times. But it would not be shocking if this did not occur. But if you rolled a thousand or a million times, then you would expect the results to match the predicted probability closely because you would expect the  One approach to time travel is to embrace timeline branching: when someone travels in time and changes something (which is inevitable), then a branch grows from the timeline. This, as was discussed in the previous essay, allows a possible solution to the grandfather paradox. But it also gives rise to various problems and questions, such as the need to account for the creation of a new universe for each timeline branch. The fact that these universes are populated also creates a problem, specifically one with personal identity. Since I used the grandfather paradox as the context previously, I will continue to do so.

One approach to time travel is to embrace timeline branching: when someone travels in time and changes something (which is inevitable), then a branch grows from the timeline. This, as was discussed in the previous essay, allows a possible solution to the grandfather paradox. But it also gives rise to various problems and questions, such as the need to account for the creation of a new universe for each timeline branch. The fact that these universes are populated also creates a problem, specifically one with personal identity. Since I used the grandfather paradox as the context previously, I will continue to do so. The grandfather problem is a classic time travel problem. Oversimplified, the problem is as follows. If time travel is possible, then a person should be able to go back in time and kill their grandfather before they have any children. But if they do, then the killer would never exist and would not be able to go back in time and kill their grandfather. So, their grandfather would not be killed and they would exist and be able to go back in time and kill him. But if they kill him, then they would not exist. And so on. There have been attempts of varying quality to solve this problem and one is to advance the notion of timeline branching. The simple version is that time is like a river and travelling back in time to change things results in the creation of a new branch of the river, flowing onward in a somewhat different direction.

The grandfather problem is a classic time travel problem. Oversimplified, the problem is as follows. If time travel is possible, then a person should be able to go back in time and kill their grandfather before they have any children. But if they do, then the killer would never exist and would not be able to go back in time and kill their grandfather. So, their grandfather would not be killed and they would exist and be able to go back in time and kill him. But if they kill him, then they would not exist. And so on. There have been attempts of varying quality to solve this problem and one is to advance the notion of timeline branching. The simple version is that time is like a river and travelling back in time to change things results in the creation of a new branch of the river, flowing onward in a somewhat different direction. Texas’ power infrastructure collapsed in the face of a winter storm, leaving many Texans in the frigid darkness. Ted Cruz infamously fled Texas in search of warmer climes, ensuring his ongoing success as an ideal Republican politician. You might expect that Texans would have responded to this disaster by addressing the underlying problems. You might, if you did not understand the Republicans of Texas.

Texas’ power infrastructure collapsed in the face of a winter storm, leaving many Texans in the frigid darkness. Ted Cruz infamously fled Texas in search of warmer climes, ensuring his ongoing success as an ideal Republican politician. You might expect that Texans would have responded to this disaster by addressing the underlying problems. You might, if you did not understand the Republicans of Texas. In the context of the war on “cancel culture” Republicans professes devotion to the First Amendment, freedom of expression and the marketplace of ideas. As noted in earlier essays, they generally frame such battles in disingenuous ways or lie. For example, Republicans raged against the alleged cancellation of Dr. Seuss, but the truth is Dr. Seuss’ estate decided to stop selling six books. As another example, Republicans went into a frenzy when Hasbro renamed their Mr. Potato Head product line to “Potato Head” while keeping Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head. In these cases, the companies were not forced to do anything, and these seemed to be marketing decisions based on changing consumer tastes and values.

In the context of the war on “cancel culture” Republicans professes devotion to the First Amendment, freedom of expression and the marketplace of ideas. As noted in earlier essays, they generally frame such battles in disingenuous ways or lie. For example, Republicans raged against the alleged cancellation of Dr. Seuss, but the truth is Dr. Seuss’ estate decided to stop selling six books. As another example, Republicans went into a frenzy when Hasbro renamed their Mr. Potato Head product line to “Potato Head” while keeping Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head. In these cases, the companies were not forced to do anything, and these seemed to be marketing decisions based on changing consumer tastes and values. Another technique is the emphasis. When numbers are used, presenting them with the positive or negative statement can influence people. So, saying 52% of Americans own stocks makes it sound good. But saying 48% of Americans do not own stocks makes it sound bad. Looked at neutrally, 48% is a significant lack. After all, if 48% of Americans lacked shelter or adequate food, we would hardly rejoice that 52% had those things. So, gushing about 52% of Americans owning stock is a bit absurd.

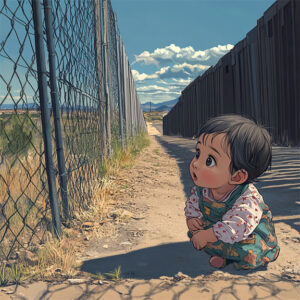

Another technique is the emphasis. When numbers are used, presenting them with the positive or negative statement can influence people. So, saying 52% of Americans own stocks makes it sound good. But saying 48% of Americans do not own stocks makes it sound bad. Looked at neutrally, 48% is a significant lack. After all, if 48% of Americans lacked shelter or adequate food, we would hardly rejoice that 52% had those things. So, gushing about 52% of Americans owning stock is a bit absurd. In addition to being evil, bigotry also tends to be repetitive. For example, racists and xenophobes have relentlessly claimed that migrants are diseased job stealing criminals. This has gone on so long in the United States that descendants of migrants who were subject to these bigoted attacks are now using them against the latest wave of migrants. Another classic is the “what about the children!” tactic.

In addition to being evil, bigotry also tends to be repetitive. For example, racists and xenophobes have relentlessly claimed that migrants are diseased job stealing criminals. This has gone on so long in the United States that descendants of migrants who were subject to these bigoted attacks are now using them against the latest wave of migrants. Another classic is the “what about the children!” tactic.