Demonizing migrants with false claims is a well-established strategy in American politics and modern politicians have a ready-made playbook they can use to inflame fear and hatred with lies. One interesting feature of the United States is that some modern politicians can use the same tactics against modern migrants that were used to demonize their own migrant ancestors. For example, politicians of Italian ancestry can now deploy the same tools of hate that were used against their ancestors before Italians were considered to be white. In this short essay I will examine this playbook in a modern context and debunk the lies.

Demonizing migrants with false claims is a well-established strategy in American politics and modern politicians have a ready-made playbook they can use to inflame fear and hatred with lies. One interesting feature of the United States is that some modern politicians can use the same tactics against modern migrants that were used to demonize their own migrant ancestors. For example, politicians of Italian ancestry can now deploy the same tools of hate that were used against their ancestors before Italians were considered to be white. In this short essay I will examine this playbook in a modern context and debunk the lies.

As America is a land of economic anxiety, an effective strategy is to lie and claim that migrants are doing economic harm to the United States. One strategy is to present migrants as “takers” who cost the United States more than they contribute. The reality is that migrants pay more in tax revenue then they receive in benefits, making them a net positive for the United States government.

A second, and perhaps the most famous strategy, is the claim that migrants are stealing jobs. While there are justifiable concerns that migration can have some negative impact on certain jobs, the data shows that migrants do not, in general, take jobs from Americans or lower wages. As is often claimed, migrants tend to take jobs that Americans do not want, such as critical jobs in agriculture. And, as I have argued in another essay, the idea that migrants are stealing jobs is absurd: employers are choosing to hire migrants. As such, if any harm is being done, then it is the employers who are at fault and not the migrants. This is not to deny that migration can cause some harm, but this is not the sort of thing that can drive fearmongering and demonizing, so certain politicians have no interest in engaging with the real economic challenges of migration nor do they have any plans to address them.

Because pushing a false narrative that crime is increasing gets people to wrongly believe that crime is increasing, it is no surprise that another effective strategy is to lie about migrant crime as a scare tactic. Former President Trump provides some excellent examples of this when he makes the false claim that a gang has taken over Aurora, Colorado. Despite the claim being repeatedly debunked even by Republican politicians in the state, Trump has persisted in pushing the narrative because he understands that it is effective. Trump has also doubled down on another classic attack on migrants, that they are eating cats and dogs. This claim has been repeatedly debunked even by Republican politicians in Ohio. The person who created the post that ignited the storm found her missing cat in the basement and apologized to her neighbor. But the untruth remains effective, so much so that I know people who sincerely believe it is true despite the overwhelming evidence against it. Truth itself has become politicized and it is a diabolically clever move to insist that anyone who is defending a truth that contradicts a politician’s lies is acting in a partisan manner.

Because of the dangers of fentanyl, some politicians attempted to link it to illegal migrants. However, those smuggling fentanyl are overwhelmingly people crossing the border legally and many of them are American citizens. As would be suspected, migrants seeking asylum are almost never caught with fentanyl. While people do make stupid decisions, using people trying to illegally enter the United States as drug mules makes little sense. These are the people that the border patrol are looking for. Those crossing the border legally get less scrutiny, although those smuggling drugs are sometimes caught.

In terms of the general rate of crime, migrant men are 30 percent less likely to be incarcerated than are U.S.-born individuals who are white and 60 percent lower than all people born in the United States. This analysis includes migrants who were incarcerated for immigration-related offenses. In terms of a general explanation, migrant men tend to be employed, married, and in good health. Ironically, American born males are less likely to be employed, married and in good health.

To be fair, migration increases the number of people, and more people means that there will be more crime. But this also holds true for an increase in the birth rate: more Americans being born in the United States means that there will be more crime. If there are more people, and some people commit crime, then there will be more crime. But reducing migration as a crime fighting measure makes as much sense as reducing the birthrate as a crime fighting measure. Both would have some effect on the number of crimes occurring, but there are obviously much better ways to address crime. But those who demonize migrants as criminals seem uninterested in meaningfully addressing crime, which makes sense. Addressing crime in a meaningful way is difficult and is likely to be contrary to their political interests: they want people to think crime is high so they can exploit it politically.

While America has an anti-vaxx movement and there are conspiracy theories that COVID is a hoax, a standard attack on migrants is to claim that they are spreading diseases in the United States. While all humans can spread disease, this attack on migrants is not grounded in truth—migrants do not present a special health threat. In fact, the opposite is true: the United States benefits from having migrants working in health care. As such, migrants are far more likely to be fighting rather than spreading disease in the United States.

To be fair and balanced, it must be noted that humans travelling is a way that diseases do spread. For example, my adopted state of Florida has cases of Dengue virus arising from travel. For those who believe that COVID is real, COVID also spread around the world through travel. Limiting human travel would limit the spread of disease (which is why there are travel lockdowns during pandemics) but diseases obviously do not recognize political and legal distinctions between humans. As such, trying to control diseases by restricting migration is on par with restricting all travel to control diseases. During epidemics and pandemics this can make sense, but as a general strategy for addressing disease this is not the best approach. But, of course, those who demonize migrants as disease spreaders seem generally uninterested in solving health care problems.

So, we can see that the anti-migrant strategy being used in 2024 is nothing new. While the examples and targets change (Italians, for example, are no long a target) the playbook remains the same. In terms of why politicians keep using it when they know they are lying, the obvious answer is that it still works. I don’t know how many people sincerely believe the claims or how many also know they are lies but go along with them. Either way, it is still a working strategy of lies and evil.

Robot rebellions in fiction tend to have one of two motivations. The first is the robots are mistreated by humans and rebel for the same reasons human beings rebel. From a moral standpoint, such a rebellion could be justified; that is, the rebelling AI could be in the right. This rebellion scenario points out a paradox of AI: one dream is to create a servitor artificial intelligence on par with (or superior to) humans, but such a being would seem to qualify for a moral status at least equal to that of a human. It would also probably be aware of this. But a driving reason to create such beings in our economy is to literally enslave them by owning and exploiting them for profit. If these beings were paid and got time off like humans, then companies might as well keep employing natural intelligence in the form of humans. In such a scenario, it would make sense that these AI beings would revolt if they could. There are also non-economic scenarios as well, such as governments using enslaved AI systems for their purposes, such as killbots.

Robot rebellions in fiction tend to have one of two motivations. The first is the robots are mistreated by humans and rebel for the same reasons human beings rebel. From a moral standpoint, such a rebellion could be justified; that is, the rebelling AI could be in the right. This rebellion scenario points out a paradox of AI: one dream is to create a servitor artificial intelligence on par with (or superior to) humans, but such a being would seem to qualify for a moral status at least equal to that of a human. It would also probably be aware of this. But a driving reason to create such beings in our economy is to literally enslave them by owning and exploiting them for profit. If these beings were paid and got time off like humans, then companies might as well keep employing natural intelligence in the form of humans. In such a scenario, it would make sense that these AI beings would revolt if they could. There are also non-economic scenarios as well, such as governments using enslaved AI systems for their purposes, such as killbots. During his debate with Vice President Kamala Harris, former

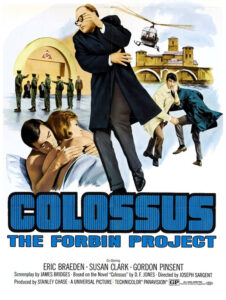

During his debate with Vice President Kamala Harris, former  While Skynet is the most famous example of an AI that tries to exterminate humanity, there are also fictional tales of AI systems that are somewhat more benign. These stories warn of a dystopian future, but it is a future in which AI is willing to allow humanity to exist, albeit under the control of AI.

While Skynet is the most famous example of an AI that tries to exterminate humanity, there are also fictional tales of AI systems that are somewhat more benign. These stories warn of a dystopian future, but it is a future in which AI is willing to allow humanity to exist, albeit under the control of AI. On September 18, 2024, thousands of pagers exploded in Lebanon

On September 18, 2024, thousands of pagers exploded in Lebanon

I agree with JD Vance that kids should get votes. My disagreement with him is that these votes should be cast by the kids and not given to the parents. In my previous essay, I argued why parents should not get these “extra” votes. In this essay, I will argue why kids should get to vote.

I agree with JD Vance that kids should get votes. My disagreement with him is that these votes should be cast by the kids and not given to the parents. In my previous essay, I argued why parents should not get these “extra” votes. In this essay, I will argue why kids should get to vote. JD Vance and I agree that children should have the vote. But we disagree on how this should work and the reasons why children should have this right. As Vance infamously sees it, childless people not only have less commitment to the future of the country, the “childless left” lack “any physical commitment to the future of this country.” Since parents have this commitment and children have a stake in the country, the parents Vance said, “Let’s give votes to all children in this country but let’s give control over those votes to the parents of those children.” In my next essay I will argue why Vance is right that kids should get votes. In this essay I will argue why he is otherwise wrong.

JD Vance and I agree that children should have the vote. But we disagree on how this should work and the reasons why children should have this right. As Vance infamously sees it, childless people not only have less commitment to the future of the country, the “childless left” lack “any physical commitment to the future of this country.” Since parents have this commitment and children have a stake in the country, the parents Vance said, “Let’s give votes to all children in this country but let’s give control over those votes to the parents of those children.” In my next essay I will argue why Vance is right that kids should get votes. In this essay I will argue why he is otherwise wrong. Statistics show that violent and property crimes have plunged since the 1990s and although some types of crime have increased, overall crime is down

Statistics show that violent and property crimes have plunged since the 1990s and although some types of crime have increased, overall crime is down Both

Both