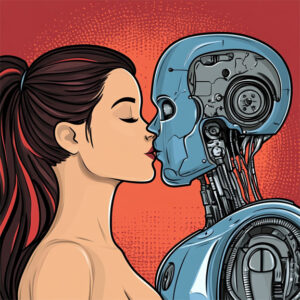

While science fiction has speculated about robot-human sex and romance, current technology offers little more than sex dolls. In terms of the physical aspects of sexual activity, the development of more “active” sexbots is an engineering problem; getting the machinery to perform properly and in ways that are safe for the user (or unsafe, if that is what one wants). Regarding cheating, while a suitably advanced sexbot could actively engage in sexual activity with a human, the sexbot would not be a person and hence the standard definition of cheating (as discussed in the previous essays) would not be met. This is because sexual activity with such a sexbot would be analogous to using any other sex toy (such as a simple “blow up doll” or vibrator). Since a person cannot cheat with an object, such activity would not be cheating. Some people might take issue with their partner sexing it up with a sexbot and forbid such activity. While a person who broke such an agreement about robot sex would be acting wrongly, they would not be cheating. Unless, of course, the sexbot was enough like a person for cheating to occur.

While science fiction has speculated about robot-human sex and romance, current technology offers little more than sex dolls. In terms of the physical aspects of sexual activity, the development of more “active” sexbots is an engineering problem; getting the machinery to perform properly and in ways that are safe for the user (or unsafe, if that is what one wants). Regarding cheating, while a suitably advanced sexbot could actively engage in sexual activity with a human, the sexbot would not be a person and hence the standard definition of cheating (as discussed in the previous essays) would not be met. This is because sexual activity with such a sexbot would be analogous to using any other sex toy (such as a simple “blow up doll” or vibrator). Since a person cannot cheat with an object, such activity would not be cheating. Some people might take issue with their partner sexing it up with a sexbot and forbid such activity. While a person who broke such an agreement about robot sex would be acting wrongly, they would not be cheating. Unless, of course, the sexbot was enough like a person for cheating to occur.

There are already efforts to make sexbots more like people in terms of their “mental” functions. For example, being able to create the illusion of conversation via AI. As such efforts progress and sexbots act more and more like people, the philosophical question of whether they really are people will become increasingly important to address. While the main moral concerns would be about the ethics of how sexbots are treated, there is also the matter of cheating.

If a sexbot were a person, then it would be possible to cheat with them; just as one could cheat with an organic person. The fact that a sexbot might be purely mechanical would not be relevant to the ethics of the cheating, what would matter would be that a person was engaging in sexual activity with another person when their relationship with another person forbids such behavior.

It could be objected that the mechanical nature of the sexbot would matter because sex requires organic parts of the right sort and thus a human cannot really have sex with a sexbot, no matter how the parts of the robot are shaped.

One counter to this is to use a functional argument. To draw an analogy to the philosophy of mind known as functionalism, it could be argued that the composition of the relevant parts does not matter, what matters is their functional role. A such, a human could have sex with a sexbot that had parts that functioned in the right way.

Another counter is to argue that the composition of the parts does not matter, rather it is the sexual activity with a person that matters. To use an analogy, a human could cheat on another human even if their only sexual contact with the other human involved sex toys. In this case, what matters is that the activity is sexual and involves people, not that objects rather than body parts are used. As such, sex with a sexbot person could be cheating if the human was breaking their commitment.

While knowing whether a sexbot is a person would (mostly) settle the cheating issue, there remains the epistemic problem of other minds. In this case, the problem is determining whether a sexbot has a mind that qualifies them as a person. There can, of course, be varying degrees of confidence in the determination and there could also be degrees of personness. Or, rather, degrees of how person-like a sexbot might be.

Thanks to Descartes and Turing, there is a language test for having a mind. If a sexbot can engage in conversation that is indistinguishable from conversation with a human, then it would be reasonable to regard the sexbot as a person. That said, there might be good reasons for having a more extensive testing system for personhood which might include testing for emotions and self-awareness. But, from a practical standpoint, if a sexbot can engage in a level of behavior that would qualify them for person status if they were a human capable of that behavior, then it would be just as reasonable to accept the sexbot as a person. To do otherwise would seem to be mere prejudice. As such, a human person could cheat with a sexbot that could pass this test. At least it would be cheating as far as we knew.

Since it will be a long time (if ever) before a sexbot person is constructed, what is of immediate concern are sexbots that are person-like. That is, they do not meet the standards that would qualify a human as a person, yet have behavior that is sophisticated enough that they seem to be more than objects. One might consider an analogy here to animals: they do not qualify as human-level people, but their behavior does qualify them for a moral status above that of objects (at least for most moral philosophers and all decent people). In this case, the question about cheating becomes a question of whether the sexbot is person-like enough to enable cheating to take place.

One approach is to consider the matter from the perspective of the human. If the human engaged in sexual activity with the sexbot regards them as being person-like enough, then the activity can be seen as cheating because they would believe they are cheating. An objection to this is that it does not matter what the human thinks about the sexbot, what matters is its actual status. After all, if a human regards a human they are cheating with as an object, this does not mean they are not cheating. Likewise, if a human feels like they are cheating, it does not mean they really are.

This can be countered by arguing that how the human feels does matter. After all, if the human thinks they are cheating and they are engaging in the behavior, they are still acting wrongly. To use an analogy, if a person thinks they are stealing something and takes it anyway, they have acted wrongly even if it turns out that they were not stealing. The obvious objection to this line of reasoning is that while a person who thinks they are stealing did act wrongly by engaging in what they thought was theft, they did not actually commit a theft. Likewise, a person who thinks they are engaging in cheating, but are not, would be acting wrongly in that they are doing something they think is wrong, but not cheating.

Another approach is to consider the matter objectively so that the degree of cheating would be proportional to the degree that the sexbot is person-like. On this view, cheating with a person-like sexbot would not be as bad as cheating with a full person. The obvious objection is that one is either cheating or not; there are no degrees of cheating. The obvious counter is to try to appeal to the intuition that there could be degrees of cheating in this manner. To use an analogy, just as there can be degrees of cheating in terms of the sexual activity engaged in, there can also be degrees of cheating in terms of how person-like the sexbot is.

While person-like sexbots are still the stuff of science fiction, I suspect the future will see some interesting divorce cases in which this matter is debated in court.