As J.S. Mill noted in On Liberty, people usually do not approach questions of freedom in a principled and consistent way. Instead, they support or oppose restrictions based on feelings. The subject of abortion presents an example of this sort of thing.

As J.S. Mill noted in On Liberty, people usually do not approach questions of freedom in a principled and consistent way. Instead, they support or oppose restrictions based on feelings. The subject of abortion presents an example of this sort of thing.

Conservatives claim they oppose regulations and favor liberty; yet usually support imposing strict restrictions on abortion. Liberals claim to favor regulations protecting people, yet usually at least tolerate a right to abortion. These seeming inconsistencies raise the problem of developing a consistent moral position on liberty and regulation. I will begin with the stereotypical conservative and move on to their liberal counterpart while noting that there are nuanced positions.

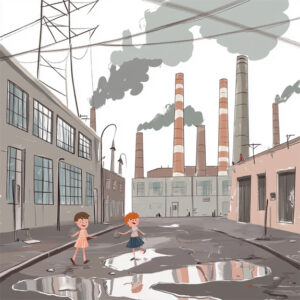

While it is a stereotype, conservatives often claim to oppose many regulations intended to protect people from harm. For example, environmental regulations are supposed to protect people from pollution. As another example, safety regulations for workplaces are intended to protect workers. Few conservatives will claim they are against protecting people but they often argue against such regulations by claiming they harm business, “kill” jobs and limit profits. Some also claim the dangers of things like pollution are fabrications by liberals who are motivated by their hatred of capitalism.

Pushing aside the rhetoric, an objective look at the stereotypical conservative stance on protective regulation is that they are willing to tolerate harms, such as the deaths of children from pollution, as part of cost of business. This is a utilitarian/consequentialist approach: a certain amount of harm (pollution, safety issues, health problems, etc.) is an acceptable price to pay for economic advantages. This is also a cost-shifting approach: the cost is moved from the business to those hurt by weak or absent regulations. For example, weak regulations on pollution and environmental damage allow businesses to make more profits because they do not need to pay the full costs of these harms. They are instead shifted on to the people hurt by them. The idea is, in general terms, that the interests of business outweigh the interests of those harmed even when those harmed are the unborn and young children. This is a classic consequentialist approach for resolving competing interests.

Conservatives usually claim to oppose abortion based on moral and religious views that life is sacred or that the unborn must be protected. They do not present it as imposing on liberty. The problem with this position on abortion is that it directly contradicts their professed position on regulations aimed at protecting people: they oppose such regulations by arguing in favor of economic interests. Obviously, if it is acceptable to allow harm to the unborn when doing so is in the economic interest of those doing the harm, this general principle must also be applied to abortion as well. It should be acceptable when the interest of the woman outweighs that of the unborn. Put in crude terms, if a business should be allowed to kill children so it can make a slighter larger profit, then women should be allowed to have abortions.

This reasoning can be countered on utilitarian grounds: allowing businesses to harm to the unborn for economic interests outweighs the harms; allowing women to have abortions when it is in their interest does not. This could also be argued by contending that women matter less (or not at all) in the calculation, unless they are in business and harming the unborn via business activity. This approach, while honest, does seem terrible: the unborn should not be harmed, unless doing so is profitable for the right economic interests. Liberals also run into a problem here.

While it is a stereotype, liberals are supposed to favor regulation that protects people, even when doing so imposes economic costs. They are also supposed to be pro-choice and support the liberty of a woman to have an abortion.

When arguing for protective regulations, one approach is to do so on utilitarian grounds: protecting people from harm creates more good than bad, even when the economic harms are factored in. There is also the fairness argument: when businesses can shift the costs to the people being harmed by their activities, this is stealing from those people. And, of course, there is the more deontological approach (that actions are good or bad in themselves) that allowing people to be harmed is just wrong.

The utilitarian justification can be used to justify abortion: the benefits gained outweigh the harm done. But probably not for the unborn, though. This suggests that the same approach can also justify opposing protective regulations: if it is acceptable to kill the unborn when doing so is in one’s interest, then this would apply both to a woman having an abortion and businesses killing them through, for example, pollution.

The fairness argument seems to tell against abortion: the cost is being imposed on the unborn as they are killed for the interests of another. This seems analogous to cost shifting in business. The deontological approach would also seem to tell against abortion: if regulation is needed to protect the unborn from the harm of pollution and such, then it would also be needed to protect them from abortion.

It is important to note that I am not addressing which position is correct. Rather, my objective has been to map out the conflict between views of protective regulations and abortion. Pro-life folks should be for protective regulation or have a reasonable argument why aborting the unborn is wrong but killing them through environmental pollution is acceptable. Pro-choice folks should be tolerant of the liberty to harm others when doing so is in one’s interest or have a reasonable argument why aborting the unborn is acceptable but harming them with pollution is not.

Well, sure. Mill’s characterization is old. *Feelings* are how we think about stuff. My idea concerning interests, motives and preferences goes a little deeper (I hope) into describing a CONTEXTUAL REALITY (CR) approach. I never bought Mill’s utilitarianism….think it was/is phony baloney. Ergo,history, notwithstanding, my thinking tells me the ideas of Mill and Marx were in cahoots… phony baloney supports itself, due, in part, to ignorance. CR identifies reality as whatever adherents say it is. The new administration seeks to legitimize corruption because it says all is well. No. All is not well. I grow weary, stating the obvious.

Mill was first, yes? Marx was a piker… hmmmm… I won’t re-visit here, anything else I have formerly asserted.