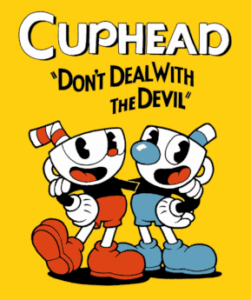

Inuendo Studios presents an excellent and approachable analysis of the infamous Gamer Gate and its role in later digital radicalization. This video inspired me to think about manufactured outrage, which reminded me of the fake outrage over such video games as Cuphead and Doom. There was also similar rage against the She-Ra and He-Man reboots. Mainstream fictional outrage against fiction involved the Republican’s rage against Dr. Seuss being “cancelled.” Unfortunately, fictional outrage can lead to real consequences, such as death threats, doxing, swatting, and harassment. In politics fictional outrage is weaponized for political gain, widens the political divide between Americans, and escalates emotions. In short, fictional outrage at fiction makes reality worse.

I call this fictional outrage at fiction for two reasons. The first is that the outrage is fictional: it is manufactured and based on untruths. The second is that the outrage is at works of fiction, such as games, TV shows, movies, and books. Since Thought Slime, Innuendo Studios, Shaun, and others have ably gone through examples in detail, I will focus on some of the rhetorical and fallacious methods used in fictional outrage at fiction. These methods also apply to non-fiction targets as well, but I am mainly interested in fiction here. Part of my motivation is to show that some people put energy into enraging others about make-believe things like games and TV shows. While fiction is subject to moral evaluation, it should be remembered that it is fiction. Although our good dead friend Plato would certainly take issue with my view.

While someone can generate fictional outrage by complete lies, this is usually less effective than using some residue of truth. Hyperbole is an effective tool for this task. Hyperbole is usually distinguished from outright lying because hyperbole is an exaggeration rather than a complete fabrication. For example, if someone says they caught a huge fish they would be simply lying if they caught nothing but would be using hyperbole if they caught a small fish. There can be debate over what is hyperbole and what is simply a lie. For example, when the Dr. Seuss estate decided to stop publishing six books, the Republicans and their allies claimed Dr. Seuss had been cancelled by the left. While it was true that six books would not be published, it can be argued whether saying the left cancelled them is hyperbole or simply a lie. Either way, of course, the claim is not true.

Even if the target audience knows hyperbole is being used, it can still influence their emotions, especially if they want to believe. So, even if someone recognizes that the “wrongdoing” of a games journalist was absurdly exaggerated, they might still go along with the outrage. A person who is particularly energetic and dramatic in their hyperbole can also use their showmanship to augment its impact.

The defense against hyperbole is, obviously, to determine the truth of the matter. One should always be suspicious of claims that seem extreme or exaggerated, although they should not be automatically dismissed as extreme claims can be true. Especially since we live in a time of extremes.

A common fallacy used in fictional outrage is the Straw Man. This fallacy is committed when someone ignores an actual position, claim or action and substitutes a distorted, exaggerated, or misrepresented version of it. This fallacy often involves hyperbole. This sort of “reasoning” has the following pattern:

- Person A has position X/makes claim X/did X.

- Person B presents Y (which is a distorted version of X).

- Person B attacks Y.

- Therefore, X is false/incorrect/flawed/wrong.

This sort of “reasoning” is fallacious because attacking a distorted version of something does not constitute an attack on the thing itself. One might as well expect an attack on a drawing of a person to physically harm the person. To illustrate the way the fallacy is often used, consider what happened to start the “outrage” over Cuphead. A writer played an early version of the game badly, noted that they were doing badly, and were generally positive about the game. All this was ignored by those wanting to manufacture rage: they presented it as a game journalist condemning the game for being too hard because they are bad at games. And it escalated from there.

The Straw Man fallacy is an excellent way to manufacture rage; one can simply create whatever custom villain they wish by distorting reality. As with hyperbole, there is the question of what distinguishes a straw man from a complete fabrication; the difference is that the Straw Man fallacy starts with some truth and then distorts it. To use the Cuphead example, if a person had never even played Cuphead or said anything about it, saying that they hated the game because they are incompetent would be a complete fabrication rather than a straw man.

Straw Man attacks tend to work because people generally do not bother to investigate the accuracy of claims they want to believe; and even if they are not already invested in the claim, checking a claim takes some effort. It is easier to just believe (or not) without checking. People also often expect others to be truthful, which is increasingly unwise.

The defense against a Straw Man is to check the facts. Ideally this would involve going to the original source or at least using a credible and objective source.

A third common fallacy used in fictional outrage is Hasty Generalization. This fallacy is committed when a person draws a conclusion about a population based on a sample that is not large enough. It has the following form:

Premise 1. Sample S, which is too small, is taken from population P.

Conclusion: Claim C is drawn about Population P based on S.

The person committing fallacy is misusing the following type of reasoning, which is known as Inductive Generalization, Generalization, and Statistical Generalization:

Premise 1: X% of all observed A’s are B’s.

Premise : Therefore X% of all A’s are B’s.

The fallacy is committed when not enough A’s are observed to warrant the conclusion. If enough A’s are observed, then the reasoning is not fallacious. Since Hasty Generalization is committed when the sample (the observed instances) is too small, it is important to have samples that are large enough when making a generalization.

This fallacy is useful in creating fictional outrage because it enables a person to (fallaciously) claim that something is widespread based on a small sample. If the sample is extremely small and it is a matter of an anecdote, then a similar fallacy, Anecdotal Evidence, can be committed. This fallacy is committed when a person draws a conclusion about a population based on an anecdote (a story) about one or a very small number of cases. The fallacy is also committed when someone rejects reasonable statistical data supporting a claim in favor of a single example or small number of examples that go against the claim. The fallacy is considered by some to be a variation of Hasty Generalization. It has the following forms:

Form One

Premise 1: Anecdote A is told about a member (or small number of members) of Population P.

Conclusion: Claim C is made about Population P based on Anecdote A.

Form Two

- Reasonable statistical evidence S exists for general claim C.

- Anecdote A is presented that is an exception to or goes against general claim C.

- Conclusion: General claim C is rejected.

People often fall victim to this fallacy because stories and anecdotes have more psychological influence than statistical data. This leads people to infer that what is true in an anecdote must be true of the whole population or that an anecdote justifies rejecting statistical evidence. Not surprisingly, people usually accept this fallacy because they prefer that what is true in the anecdote be true in general. For example, if one game journalist is critical of a game because it has sexist content, then one might generate outrage by claiming that all game journalists are attacking all games for sexist content.

A person can also combine rhetorical tools and fallacies. For example, an outrage merchant could use hyperbole to create a straw man of an author who wrote a piece about whether video game characters should be more diverse and less stereotypical. The straw man could be something like this author wants to eliminate white men from video games and replace them with women and minorities. This straw man could then be used in the fallacy of Anecdotal Evidence to “support” the claim that “the left” wants to eliminate white men from video games and replace them with women and minorities.

The defense against Hasty Generalization and Anecdotal Evidence is to check to see if the sample size warrants the conclusion being drawn. One way that people try to protect their claims from such scrutiny is to use an anonymous enemy. This is done by not identifying their sample’s members but referring to a vague group such as “those people”, “the left”, “SJWs”, “soy boys”, “the woke mob”, or whatever. If pressed for specific examples that can be checked, a common tactic is to refer to someone who has been targeted by a straw man fallacy and just use Anecdotal Evidence again. Another common “defense” is to respond with anger and simply insist that there are many examples, while never providing them. Another tactic used here is Headlining.

In this context, Headlining occurs when someone looks at the headline of an article and then speculates or lies about the content. These misused headlines are often used as “evidence”, especially to “support” straw man claims. For example, an article might be entitled “Diversity and Inclusion in Video Games: A Noble Goal.” The article could be a reasoned and balanced piece on the merits and cons of diversity and inclusion in video games. But the person who “headlines” it (perhaps by linking to it in a video or including just a screen shot) could say that the piece is a hateful screed about eliminating white men from video games. This can be effective for the same reason that the standard Straw Man is effective; few people will bother to read the article. Those who already feel the outrage will almost certainly not bother to check; they will simply assume the content is as claimed (or perhaps not care).

There are many other ways to create fictional outrage at fiction, but I hope this is useful in increasing your defense against such tactics.