Back in the last pandemic, lawsuits were filed by some religious groups because of restrictions imposed in response to COVID-19. If the government imposes similar restrictions during a future pandemic, this will happen again. One concern about such lawsuits is that churches were super spreaders of COVID-19. An interesting consideration is that while politicians have made a religious freedom issue out of the COVID restrictions, most Americans (including religious Americans) did not see these restrictions as a threat to religious freedom. The issue is whether these sorts of pandemic restrictions violate religious freedom. I will focus on the moral issue and leave the legal issue to the lawyers.

Back in the last pandemic, lawsuits were filed by some religious groups because of restrictions imposed in response to COVID-19. If the government imposes similar restrictions during a future pandemic, this will happen again. One concern about such lawsuits is that churches were super spreaders of COVID-19. An interesting consideration is that while politicians have made a religious freedom issue out of the COVID restrictions, most Americans (including religious Americans) did not see these restrictions as a threat to religious freedom. The issue is whether these sorts of pandemic restrictions violate religious freedom. I will focus on the moral issue and leave the legal issue to the lawyers.

As a starting point, religious freedom is not absolute and can be justly restricted in at least some cases. As a general argument, unrestricted freedom would restrict (or destroy) itself. To use a silly example, if religious freedom was absolute, then the religious freedom of a religion that wanted to restrict all other religions on religious grounds must also be respected. This is a reductio on the idea of absolute freedom (and one I stole from Thomas Hobbes). As such, religious freedom requires some restrictions on religious freedom. If so, then what we need to settle is the limit (or the extent) of religious freedom and see where pandemic restrictions fall.

Intuitively, we all probably agree that religious freedom should not allow people to engage in such things as murder, theft, rape, and genocide. So, if the Church of Murder, Rape and Robbery insisted they had the moral right to rob, rape and murder you on the grounds of religious liberty you would, I assume, disagree. And rightfully so. Sticking within a rights theory of ethics, your right to life and property would override their right to religious liberty. This rests on the notion that there is a hierarchy of rights, with some rights having more moral weight than others (among other factors). One could also use a utilitarian approach of the sort developed by Mill: if restricting religious liberty would create more positive value than negative value, then doing so would be morally right. While the members of the Church of Murder, Rape and Robbery would be unhappy about not being able to practice their faith on other people, the harm this would inflict outweighs their unhappiness.

I am not claiming that wanting a religious freedom exemption from pandemic restrictions is analogous to wanting the freedom to murder, rape and rob. My point is to establish that limiting religious freedom to protect other rights and to prevent harm can be morally acceptable. But this does not settle the specific issue of whether pandemic restrictions would violate religious freedom. Obviously, this will depend on the specific restrictions and the context.

One relevant factor is the intent of restrictions. If restrictions were created and applied intending to infringe on religious liberty, then that would be wrong. But even if the restrictions were created and applied with only benign intent, they could still violate religious liberty. To use an analogy, one might impose restrictions on high calorie drinks from a benign intent (to reduce obesity) and yet still be wrongly limiting freedom. But there is no evidence that the past restrictions were created to harm religious liberty. As far as future restrictions go, they would need to be assessed.

Another relevant factor is consistency in restrictions. To illustrate, if religious gatherings were restricted because of the risk of people gathering, then fairness requires that standard be applied consistently. For example, if bars, restaurants, and movie theaters were allowed to operate normally while churches were limited, then there would a moral case that churches were being treated unfairly. The conclusion of such moral reasoning might, however, be that the bars, restaurants, and movie theaters should also be restricted rather than that the churches should not be restricted.

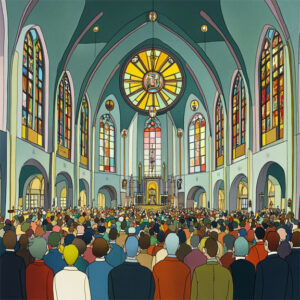

One can also make the essential service argument for churches. Grocery stores, car rental businesses and many government offices remained open because they were considered essential. The justification here is on utilitarian grounds: there would be more harm in closing them than keeping them open. To use the most obvious illustration, closing grocery stores and food delivery would result in starvation, so keeping these operating is morally acceptable. One cannot Zoom salad or download pizza. But are large, in-person gatherings at churches essential during a pandemic?

Religious is obviously important, even essential to some people. That is not in dispute. What is in dispute is whether large, in person gatherings are essential to religion. That is, can people practice their religion without being able to gather closely in large numbers. To use an analogy, running is essential to me, but large road races were restricted during the pandemic. Could I practice my running without the large gatherings of races?

On the face of it, the answer is yes. Religious people could gather online, they could gather outside and space themselves, they could gather inside in small groups wearing masks, and so on. In the case of running, I can still run by myself, I can run with others by maintaining distance, and I can do virtual races. These do involve costs and inconveniences, but they all allow people to continue to practice the group aspects of religion (and running). The fact that most religious people did these things provides evidence that religion (and running) can be practiced while restrictions are in effect. This can, of course, be disputed on theological grounds—something I will leave to the theologians. But on the face of it these restrictions did not interfere with religious liberty in a way that is unfair, inconsistent, or unwarranted relative to other freedoms, like the freedom of running.

If restrictions are applied consistently based on relevant factors such as gathering size, risk, being essential, and proximity, then the issue would become whether there should be a special religious freedom exemption from restrictions. The issue is thus whether religious freedom would allow a special exemption because religious people want to gather in ways that violate pandemic restrictions. If so, this means that there should be religious exemption in the case of public health. After all, they would not just be putting themselves at risk, they be putting everyone they contact at risk as well.

Imagine, if you will, that a person infected with Ebola insists on their religious freedom and demands they be allowed to go to church without restriction. This would be wrong: such a deadly disease could kill the others and then spread out into the community. While COVID-19 was not as lethal as Ebola, it is meaningfully dangerous. Other pandemics will come in varying degrees of lethality as well. If the next pandemic is more like COVID-19 than Ebola, perhaps it could be argued that churches should be allowed an exemption to operate normally. Churches have the right to stay open in flu season, although this does put people at risk. But we would probably all agree that people infected with Ebola should not be allowed to freely go to church because they have religious freedom. So, it is a matter of how much risk is acceptable.

To use an analogy, we all probably agree that military grade flamethrowers should not be allowed for in-church use even if a church considers fire an important part of their services. This is because flame throwers would present a danger to the people in the church and could create a fire that would spread. But imagine a church that wants something less than flamethrowers: they just want their church to be exempt from the fire safety laws and regulations that other people must follow. They argue that their religion values fire, so being forced to have things like smoke alarms, working fire extinguishers and fire exits would violate their religious freedom to practice their faith. They also want to be able to use lots of fire in their services and want to a stock of flammable material on hand, stored in loose piles around the church, as their faith demands. They would argue that there is some risk, but it is relatively low compared to flame throwers. But, of course, they could easily set their church on fire and have it spread to all the nearby structures and burn them down (and hurt the people in them). While they could be argued to have a right to burn themselves and their church, their religious freedom would not seem to give them a right to put the nearby buildings (including other churches) and the people in them at such needless risk. They can, of course, have the fire needed for their faith, but it must be kept in a way that does not needlessly risk hurting other people. The same would seem to apply to pandemic restrictions and churches: they have the right to practice their faith, but they do not have the right to put others at risk while doing so.

I don’t wade too deeply into this pond. Your final remarks are signal.