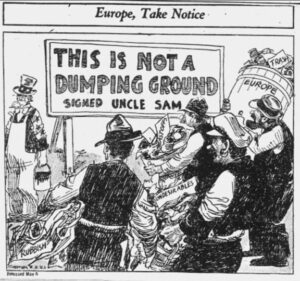

While the United States is experiencing a backlash from when Black Lives Mattered, there are still social expectations that set the allowed forms of racism. While racism is the foundation of United States immigration policy, blatantly attacking migrants for their color is considered impolite, at least for now. While there are various rhetorical approaches to attacking migrants, the focus of this essay is on the well-worn claim that migration needs to be restricted because migrants bring disease.

While the United States is experiencing a backlash from when Black Lives Mattered, there are still social expectations that set the allowed forms of racism. While racism is the foundation of United States immigration policy, blatantly attacking migrants for their color is considered impolite, at least for now. While there are various rhetorical approaches to attacking migrants, the focus of this essay is on the well-worn claim that migration needs to be restricted because migrants bring disease.

Ironically, migrants to the United States make up 16% of healthcare workers, including 29% of physicians and 24% of dentists. It is more likely that a migrant will prevent or treat a disease than cause one. If the goal is to improve health outcomes, restrictions on migration would have a negative effect. While some might worry about migration and disease in sincere ignorance, it is primarily a tool of fear and racism. But is it true that migrants present no health risks?

If the standard is that migrants must present zero health risk, then this cannot be met: there is a non-zero chance a migrant pass on an illness to an American. And it is true that migration increases the number of cases of illness: more than zero Americans will catch some illness from migrants. However, this does not warrant regarding migrants as health threat. After all, there are non-zero cases in which a migrant saves a life or does something else heroic. But it would be odd to speak of the great promise of a wave of migrant heroism—except in the economic sense. Likewise, speaking of the threat of a wave of migrant disease would is unfounded. It is also worth noting that Americans having more babies or travelling between states also increase the spreading of disease, but this is not seen as a good reason to prevent people from reproducing or travelling.

When I point out that migrants do not present a meaningful health threat, a common response is that must mean I support open borders and allowing people to flood the United States without regulation and without any concerns about their health. My reply is that this entails nothing about my view of immigration policy, except that I do not think that fears of diseased migrants should shape border policy. While I am not terrified of diseased hordes invading America, I do still have health concerns about the movement of people.

The fear that migrants can bring devastating diseases to the Americas is based on historical fact. When Europeans arrived in what they called the New World they brought with them Old World diseases that proved devastating to the native populations. Smallpox decimated the native people, thus greatly European conquest of these lands. If the natives had been able to enforce strong borders and keep the Europeans out, history would be radically different. As would be suspected, modern opponents of migration to the United States do not use this example when making their disease argument. In part this is because it would make clear that most Americans are migrants or descendants of recent migrants. There is also the fact that the situation now is different.

Back in the 1500s the native people had little or no resistance to European diseases and there was no modern medicine. The situation is different today. Migrants coming to the United States will generally not be bringing in unknown diseases that will be devastating because there is no health care. That said, we should very worried about the impact of the Trump administration on America’s fragile and overpriced health care system.

While we will be having another pandemic soon, it is unlikely to arise from migrants coming into the United States. As such, legitimate worries about pandemics do not warrant restricting general migration. After all, what generally occurs is vaccinated people migrating from countries with health care systems to the United States.

A legitimate concern is that other countries might suffer from health care failures. For example, Venezuela’s health care system was undercut due to the corruption and mismanagement of its government. One consequence was an outbreak of measles. Health care professionals have left Venezuela and its citizens have also attempted to flee. As such, we might see people fleeing a failing country with a broken health care system, thus making the spread of disease a real concern.

Normally, this sort of thing would not be a serious problem. In the case of measles, vaccination is safe and effective. It was also widespread. However, some Americans have decided to forgo vaccinating their children. America has thus intentionally made itself vulnerable to measles. While measles and other diseases will spread internally, we also need to worry about other countries failing at public health and allowing these diseases to spread. As this occurs, we might see a return to diseases spreading among unprotected populations. However, this time the lack of protection will be intentional as people will have chosen to condemn their children to illness, perhaps with the best intentions.

While proponents of the disease argument against migration will want to take advantage of these self-inflicted failures, even this scenario does not warrant the migration restrictions they favor. After all, measles is already here and does not need to be brought across the border. Rather than showing that the United States needs to tighten up the borders, this situation shows that the United States must tighten up the vaccination requirements for citizens to ensure that they are protected from diseases that are already here. Vaccines and health care, not a wall, will keep us safe from disease. While it might seem odd for the same people to push an anti-vax and “immigrants cause disease” view, this does make sense. They are both ideological movements built on fear and ignorance seemingly designed to maximize harm.