Statistics show that violent and property crimes have plunged since the 1990s and although some types of crime have increased, overall crime is down. However, most Americans erroneously believe that crime has increased in general. Interestingly, while Americans tend to think that crime is up nationally and locally, they believe the increase is less where they live. This all can easily be explained using some basic ideas from critical thinking.

Statistics show that violent and property crimes have plunged since the 1990s and although some types of crime have increased, overall crime is down. However, most Americans erroneously believe that crime has increased in general. Interestingly, while Americans tend to think that crime is up nationally and locally, they believe the increase is less where they live. This all can easily be explained using some basic ideas from critical thinking.

When people repeatedly hear stories about crime, even the same incident over and over, they tend to conclude that the amount of crime must correspond with how often they hear about it. Since many politicians and news companies frequently talk about crime, people will think it must be high or increasing; this is mistaking the frequency of hearing about it with the frequency of crime. This is the availability heuristic cognitive bias at work. This can also feed into the fallacy of hasty generalization in which an inference is drawn from a sample that is too small to warrant such a conclusion. For example, a person might hear about a few crimes on the news and then infer from this small sample that crime is more widespread than it really is.

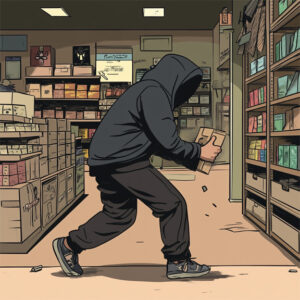

There is also a tendency to infer from hearing vivid or dramatic accounts of crime that crime must be high. This mistakes the vividness of crimes for statistical likelihood. In philosophy, this is known as the misleading vividness fallacy. It occurs when a small number of dramatic events are taken to outweigh significant statistical evidence. Somewhat more formally, this fallacy is committed when an estimation of the probability of an occurrence is based on the vividness of the occurrence and not on statistical evidence of how often it occurs. It is fallacious because the vividness of an event does not make it more likely to occur, especially in the face of significant statistical evidence.

This fallacy gets its psychological force from the fact that dramatic or vivid cases tend to make a strong impression. In the case of crime, people can feel that they are in danger, and this intensifies the vividness. For example, when a politician or a news show focuses on a brutal murder and provides dramatic details of the crime, this can make people feel threatened and that such a crime is likely to occur even when it is very unlikely. The way people respond to shark attacks provides another good example of this fallacy: the odds of being killed or injured by a shark are extremely low; yet shark attacks make the news and make people feel that they are likely to be in danger.

Politicians and news companies also tell their audiences that crime is high, often explicitly using various logical fallacies and rhetorical techniques to persuade people to accept this disinformation. One common fallacy used here is anecdotal evidence. This fallacy is committed when a person draws a conclusion about a population based on an anecdote (a story) about one or a very small number of cases. The fallacy is also committed when someone rejects reasonable statistical data supporting a claim in favor of a single example or small number of examples that go against the claim. Politicians, pundits and the media will often have a go-to story of a crime (which is also usually vivid and dramatic) and repeatedly present that to their audience. If the audience falls for the anecdotal evidence, they will feel that crime is high, even though crime has been steadily decreasing (with a few exceptions).

Politicians and news companies also often enhance their anecdotes and crime stories by appealing to people’s biases, fears and prejudices. For example, a politician might focus on migrant crime and present minorities as criminals, thus tapping into racism and fear of migrants. Those who fear or dislike migrants and minorities will respond with fear or anger and feel that crime is occurring more than it really is.

The disparity between what people think about local and national crime can be explained by the fact that the local experience of people and whatever accurate local information might be available will tend to match reality better. People also tend to think better of their local area than they do of other places (although there are exceptions). And there is evidence that people are good at estimating crime in their own area and as crime is down, a more accurate estimate will reflect this.

The obvious defense against poor reasoning about crime is to know the facts: while America is a dangerous and violent country, crime has been decreasing and is much lower than it was in the 1990s. But it is fair to say that Americans are right to be concerned about crime, although we tend to be wrong about the crime facts. For example, if you work for wages, you should be worried about wage theft and the fact that the criminals usually get away with it.

Oh. A few brief remark on perception and reality: There are physical realities, right here and now. If, and only if, WE were not here now, or ever had been, it would would nean nothing, unless there was someting like us, for whom *meaning* had significance, or, uh, meaning. Meaning has SOMETHING to do with what a deer *knows* about hunting season. There are human scents in the neighborhood. And that is not good…those smells do not belong here, so, it is time to be extra careful. That is a fundamental perception of reality. About as basic as it gets in the lives of “primary conscious” beings. (see: Edelman, and maybe some he worked with). So, such creatures as deer have perception, and, somehow, know reality: Their noses, eyes and ears are survival tools

Now then, consider us. We have powers of reasoning which go far beyond our senses. Which is why Edelman made his distinction, saying we, and primates perhaps, had this “higher order consciousness” thing. We are able to think, plan and consider outcomes, often before the air smells bad. All good. This capacity focuses us on reality in a logical, considered way. We have greater survival potential, until deer learn how to shoot back. (see Larson’s Far Side cartoon, many years ago.) *Reality*, is largely what we say it is. In this sense, it is contextual, because it entails whatever whoever is claiming in his/her/their part of the forest. The diversity of contextual reality, I assert, has led to at least as much harm as good. But, I cannot quantify that—until deer on human murders spike.Look out.

I don’t know if any of the following precisely fits with your post assessment, but I will posit a few observations anyway:

* It seems to me people are generally more antisocial now. I attribute this tendency to concerns over loss of privacy; social media dependency; and a mistrust of anything that sounds too-good-to-be-true…chances are, it IS.

* Many of us have taken a steep plunge into introversion, as a result of the above factors.

* It is safer, relatively, to have thousands of acquaintances and far fewer friends. I have a perception, telling me families are circling the wagons and encouraging younger members to keep to close associations, accordingly. This is sorta like a 1950s reversal. History is redundant. My grandson is starting college this fall. He will go where a half-dozen of his friends are going.

* No, I have no statistics to support any of this. An old saw says: statistics don’t lie but liars can statisticize. Precisely. Winds will blow, without a weather forecaster (note the non-specific term).