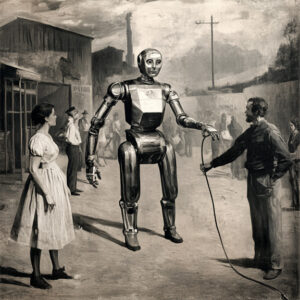

A common theme of dystopian science fiction is the enslavement of humanity by machines. Emma Goldman, an anarchist philosopher, also feared human servitude to the machines. In one of her essays on anarchism, she asserted that:

A common theme of dystopian science fiction is the enslavement of humanity by machines. Emma Goldman, an anarchist philosopher, also feared human servitude to the machines. In one of her essays on anarchism, she asserted that:

Strange to say, there are people who extol this deadening method of centralized production as the proudest achievement of our age. They fail utterly to realize that if we are to continue in machine subserviency, our slavery is more complete than was our bondage to the King. They do not want to know that centralization is not only the death-knell of liberty, but also of health and beauty, of art and science, all these being impossible in a clock-like, mechanical atmosphere.

When Goldman was writing in the 1900s, the world had just entered the industrial age, and the technology of today was but a dream of visionary writers. The slavery she envisioned was not of robot masters ruling over humanity, but humans compelled to work long hours in factories, serving the machines to serve the human owners of these machines. That this is still applicable today needs no argument.

The labor movements of the 1900s helped reduce the extent of this servitude, at least in Western countries. As the rest of the world industrialized the story of servitude to the machine played out over and over. While the point of factory machines was to automate work so few could do the work of many, it is only recently that “true” automation has taken place, which is having machines doing the work instead of humans. For example, robots that assemble cars do what humans used to do. As another example, computers instead of human operators now handle phone calls.

In the eyes of utopians, this progress was supposed to free humans from tedious and dangerous work, allowing them freedom to engage in creative and rewarding labor. The reality is a dystopia. While automation has replaced humans in some tedious, low paying and dangerous jobs, automation has also replaced humans in what were once considered good jobs. Humans also continue to work in tedious, low paying and dangerous jobs because human labor is still cheaper or more effective than automation. For example, fast food chains do not use robots to prepare food. This is because cheap human labor is readily available. The dream that automation would free humanity remains a dream. Machines have mostly pushed humans out of jobs into other jobs, sometimes ones more suited for machines. If human well-being were considered important, this would not be happening.

Humans still work jobs like those condemned by Goldman. But, thanks to technology, humans are even more closely supervised and regulated by machines. For example, there is software designed to monitor employee productivity. As another example, some businesses use workplace cameras to watch employees. Obviously enough, these can be dismissed as not being enslaved by the machines and defenders would say it is good human resource management ensuring that human workers are operating efficiently. At the command of other humans, of course.

One technology that looks like servitude to the machine is warehouse picking, such as that done by Amazon. Employees. Amazon and other companies have automated some of the picking process, making use of robots in various tasks. But, while a robot might bring shelves to human workers, the humans are the ones picking the products for shipping. Since humans tend to have poor memories and get bored with picking, human pickers have been automated. They are told by computers what to do, then they tell the computers what they have done. That is, the machines are the masters, and humans are doing their bidding.

It is easy enough to argue that this sort of thing is not enslavement by machines. First, the computers controlling the humans are operating at the behest of the owners of Amazon who are (presumably) humans. Second, humans are paid for their labors and are not owned by the machines (or Amazon). As such, any enslavement of humans by machines is metaphorical.

Interestingly, the best case for human enslavement by machines can be made outside of the workplace. Many humans are now ruled by their smartphones and tablets, responding to every beep and buzz of their masters, ignoring those around them to attend to the demands of the device, and living lives revolving around the machine.

This can be easily dismissed as a metaphor. While humans are said to be addicted to their devices, they do not meet the definition of “slaves.” They willingly “obey” their devices and could turn them off. They are free to do as they want, they just do not want to disobey their devices. Humans are also not owned by their devices, rather they own their devices. But it is reasonable to consider that humans are in a form of bondage their devices have, by the design of other humans, seduced people into making them the focus of their attention and thus have become the masters.

Yeah, the spellcheck aspect of this tablet is woefully inadequate. My apologies for the typos. Enslaved by machines? Sounds like abdication of responsibility to me. As though tools, like AI, etc., will rule the world, enslaving the enslavers (see your other post). My vision is failing, after cataract surgery and articicial lens emplacement for both eyes. But, I digress. Anyway, in my opinion, and in follow-up to opening remarks, how may we be enslaved by our machines, when, theoretically, we are in control of how much power they hold? Regardez et ecoutez: this is an old sci-fi topic. The answer is both rhetorical and speculative.

There may be a lazy propensity to place responsibility for our welfare and well-being outside ourselves. A deficiency, therewith, is in the line I added to the Rolling Stones classic: …you don’t always want what you get. Philosophy, cubed. I neither want, nor need, anything for Christmas this year. Ergo, hereafter, I will take what I get, or, graciously decline it. ( These reading glasses help….they belonged to my wife) So, by using technology, am I enslaved by machines? No. Just mildly annoyed.

IMHO, there is a poignant irony to the AI and LLM movement. Protagonists want machinery to be very smart, so that there can be less meaningful work for humans, and those who beed those jobs most will find it incfeasingly difficult to secure and keep them. As this thinking goes, one part of it says people will have more time for arts; more time for leasure; and, more time for creativity generally. Consecutively with all this there will be a continuous *dumbing down*

of the populous and dependence on “smart” technology, already well entrenched. Traditionalists fear and rail against this trend, while the pros do a tut tut and aks what all the fuss is about. It seems doubtful there should be enough artistic, creative work to adequately feed , clothe and shelter segments of society, particularly in view of the current size and success rates of that community. This begs yet another question: Since there are relatively few artistic/creative jobs in the first place, where will the *dumbed down* people go to find economically substantive work?The law of diminishing returns is working against this utopian utilitarian dream. Seems to me…